Last night I attended a forum at the Museum of Brisbane entitled Radical Houses: identity and public life in the Queensland House 1975-1989.

https://www.museumofbrisbane.com.au/whats-on/radical-houses/

Part of the inaugural Architecture and Art Week, the forum presented new research on a period of particular cultural vibrancy in Brisbane’s recent history and invited discussion of the Queenslander house as a site of public action and the making of political identity in the city.

The 1970s and 80s in Queensland are considered by many on the liberal left to have been a low point in the State’s history, often characterised as a period of quasi-fascist governance. Under conservative Premier Joh Bielke-Peterson, the state underwent a process of aggressive neo-liberalisation, similar to that of Thatcher’s UK and Reagan’s USA during the same period. In Queensland, this was accompanied by a famously oppressive regime of police harassment and brutality, underpinned by systemic corruption.

http://www.ccc.qld.gov.au/research-and-publications/publications/police/the-fitzgerald-inquiry-report-1987201389.pdf

Much of the evening was spent reminiscing about the good times. John Willsteed of celebrated Brisbane punk band the Go-Betweens offered a song.

The evening included presentations, performances, and panel discussions from several artists and musicians who were directly involved in radical activities at the time. The overarching narrative of oppression under ‘Joh and the Boys’ was apparent throughout the discussions. Several of the speakers described the political climate of the times as a “siege”. The artistic response to this was one of negation and self-destruction, or simply survival. The scrappy music and grotesque visual art they produced very closely resemble the familiar aesthetic of Punk. The DIY media publications (zines, mail art, etc) and theatre productions are steeped in anti-authoritarian satire - described simply as a political strategy of “taking the piss”.

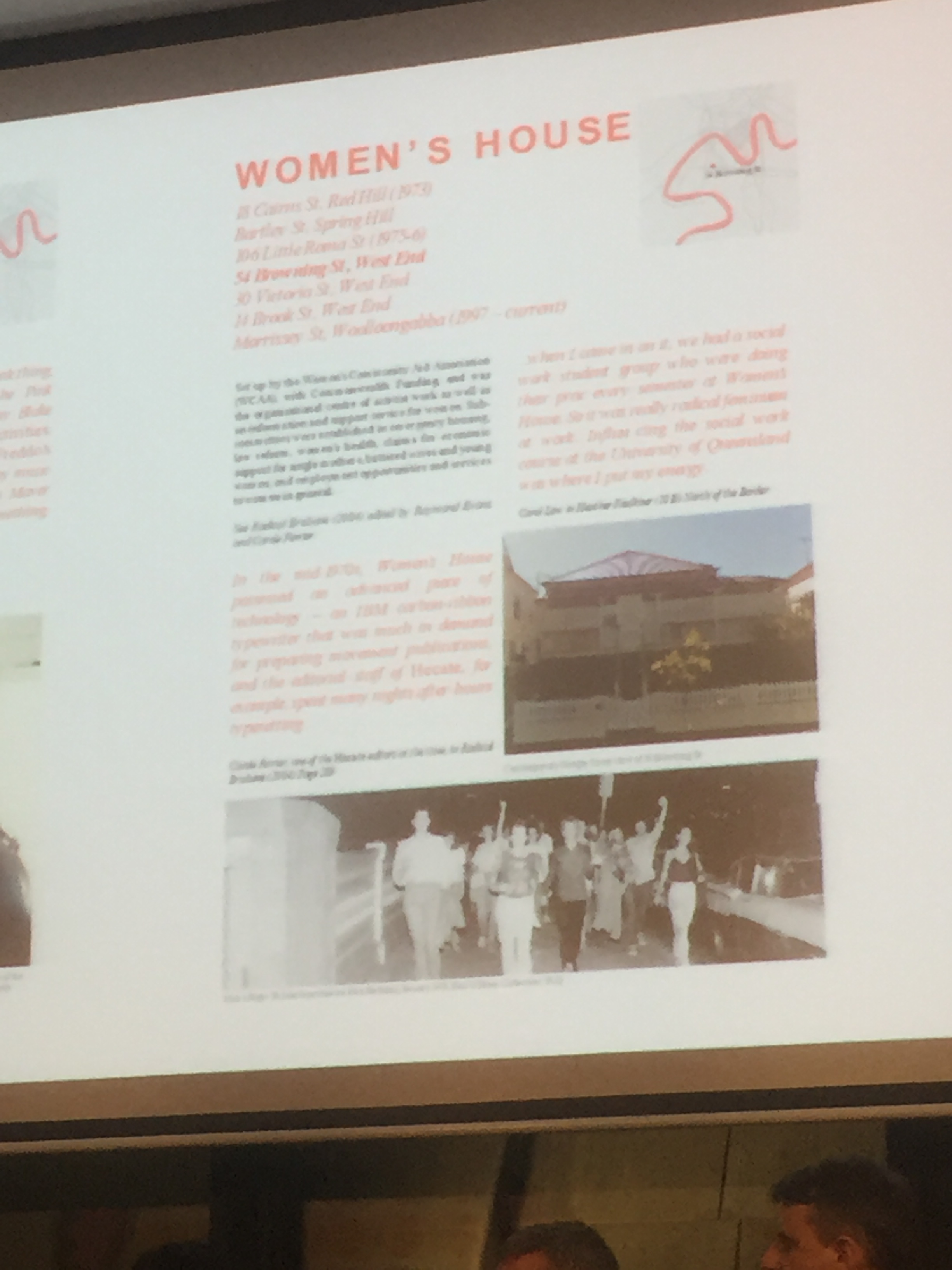

The Queenslander house was invoked as a facilitator of all this activity - cheap, inner-city, and spacious, the house became a test site for new ways of living and community-building, alongside artistic production, exhibition and performance. Against the backdrop of a suffocated civic realm, share-houses were a place to make new publics in the relative safety of the domestic realm.

Many of the panellists made this connection between the political environment and their lived artistic responses, positing that having something to fight against galvanised young people into action. However, only a few attempts were made at connecting this artistic activity back to specific political demands or progressive agendas. For many of those involved, the scope of ‘radical’ politics was simply the freedom simply to be oneself and to express one’s creative impulses. Similarly, no connection was made between the radical activity of the 1970s and 80s and the equivalent activity today. These pioneers of Brisbane’s radical housing culture laid the groundwork for a thriving underground from which important progressive art and politics continue to emerge, and yet they appear to be unaware of this legacy. By the same token, few of Brisbane’s artist-activists today make reference to their cultural inheritance or engage in direct dialogue with these radical predecessors.

The implication that young people had something to fight for ‘back then’ is that they don’t have something to fight for now. And yet, contemporary radical political and artistic movements continue to emerge from the underbellies of rented inner-city Queenslanders. People open their homes for gigs and exhibitions, everyone pitches in to build a veggie garden or cook a meal, people come and go by the open back door, the art and the music are scrappy and unfinished, the politics are personal. The parallels with the stories of the Radical Houses forum are uncanny, and yet there is an apparent failure to connect the past with the present (a recurring theme in Australian urbanism).

This disconnect raises an interesting prospect: If these ‘radical’ scenes have both effectively emerged in isolation, temporally separated but spatially overlaid, then perhaps the artistic response has less to do with the specific political context of the time and more to do with the particular qualities of the socio-spatial environment. Perhaps it is simply a case of young, well-educated people - many of whom have acquired musical or artistic training as part of their middle-class upbringing - taking advantage of the particularities of Brisbane’s built fabric and favourable property economics to do what young people do everywhere - rebel through revelry, and revel in rebellion.

Arguably the most telling moment of the evening was one response to a question regarding the relationship between the period of extraordinary cultural production described and the subsequent gentrification of the neighbourhoods in which this was taking place. Before I could finish asking what advice they might offer to younger artists and activists seeking to avoid this paradox, I was interrupted by one panellist with the words “suck it up”. She went on to describe how she and her fellow activists had intrinsically understood the value of Brisbane’s traditional built fabric, especially the Queenslander house, and thus had ultimately fought for its preservation by purchasing the homes they had once rented - an option beyond the realms of possibility even for relatively high earners of a younger generation.

This strikingly defensive response denotes a sense of entitlement that does not necessarily gel with the radical credentials put forth throughout the evening. It is an uncomfortable tension for many artist-activists that the cultural capital they generate in highlighting injustice are so often instrumentalised by injustice. However, it is much more uncomfortable to witness them disengage from the conversation altogether and resort to self-congratulatory nostalgia. People in Brisbane today do not have to contend with institutions as overtly corrupt and systematically violent as those of the past, and for that they should thank their radical predecessors. However, they still have plenty to contend with, much of it arguably more insidious - institutions that have taken on board and perfected the language of personal freedom espoused by the radicals of yesteryear, using it to sell a new image of the city to an aspirational elite of ‘global citizens’: emerging from the cultural cringe of its violent, parochial past, the new Brisbane is a veritable playground of individual consumption, a wonderland of the “creative industries” built upon deeply unsustainable forms of urban redevelopment that continue to dispossess, displace, and disintegrate marginal urban communities.