Managed to find an hour on Saturday afternoon to fly the rainbow flag from the roof of the Gabba Ward City Council office in anticipation of Brisbane Pride next weekend. Members of the grassroots activist group ‘Queer Anti-Colonial Action Bitchez’ are organising a theatrical action for the parade on Saturday.

https://www.facebook.com/events/2433955870261619/

The entry to Atlas Homes storage yard in Pinkenba. It is an unusual feature of Queenslander houses that they can be lifted and removed intact. There are around 50 houses in this yard.

The houses removed from Lytton Road as part of BCC’s Wynnum Corridor upgrade project came via Atlas. Four of the houses are still there - though soon to be find new homes around the region.

Looking for a new home

Last week I visited the Atlas Homes yard in Pinkenba, an outlying suburb, with Leo - the Temple lead, who has now come on board as a collaborator on the Backbone Festival project at EBBC. It was an odd experience, walking around houses that have literally been transplanted from their homes - the signs of recent inhabitation were many: plates in the sink, magazines on the floor, pot plants still hanging on the deck.

http://www.atlashouseremovers.com.au/

We came to look at four houses in particular which were removed from Lytton Road, in East Brisbane, as part of the road widening there.

https://www.brisbane.qld.gov.au/traffic-and-transport/roads-infrastructure-and-bikeways/current-road-and-intersection-upgrades/east-brisbane-wynnum-road-corridor-upgrade-stage-1

These are the last remaining of twelve that came through the yard, and another fourteen that were demolished are removed at an earlier stage. The story of their removal is somewhat fraught - a bitter community campaign initiated by the residents of the houses failed to persuade the municipal government to reconsider the road upgrade, despite the fact that all of the houses pre-date 1946, and were thus heritage listed.

https://www.facebook.com/groups/1727481584178372/

We were met onsite by Erin, the owner of the yard. Passionate about her work, and a prolific story-teller, Erin outlined her simple philosophy - that it was better to save these characterful old houses by removing them than to see them simply demolished and disposed of. She sits on the board of the Queensland recycling council, names each house after a relative or friend (partly as a means of keeping track of them all!), and cultivates strong personal relationships with all of her clients. While we walked around, she phoned up each of the buyers of the eight Lytton Road houses that have already been moved elsewhere. Each time she was greeted as an old friend - “how’s your mother?”, etc. It was clear that she cares deeply about what she does and about people. Before leaving, she gave us a comprehensive overview of her own family history - Irish one side and Norwegian on the other.

In conversation a few weeks ago, Councillor Sri proposed the idea that the existence of East Brisbane Bowls Club as a community space probably prevented Lytton Road from being even further widened. This wasn’t enough to save the 26 houses that were removed, however, it does draw an important link between these sites on either side of Mowbray Park. On the one hand, the loss of a community to “progress”, on the other, a community space becoming a symbol of resilience in the face of change. This has now become a key driver of the design enquiry for the EBBC set design - the collection of stories old and new, past and future, relating to this place - these houses, Backbone, and the wider East Brisbane community. The idea has immediately piqued the interest of several collaborators, who in turn have begun to conceive their own responses to this compelling story. A whole network of creatively motivated doers has been mobilised around the construction of a new mythology of place.

Only today, Leo revisited the site with Joseph Burgess, self-declared ‘unregistered master builder’ - a jack of all trades, particularly the AV tech ones. Joseph brought his photogrammetry kit and made 3D scans of the houses - their surface textures, spaces, and materials.

http://master-builder.squarespace.com/

Meanwhile I was in the city meeting with Magnus Eriksson, a management consultant who does heritage assessments as a hobby on the side. He was engaged by the soon-to-be-displaced residents to produce a heritage report for the houses being removed. It has proved to be a valuable resource in identifying relevant historical documents for the area and understanding the specific architectural styles and phases of development represented in the houses, some of which date to the 1890s.

https://www.househistories.org/

Eriksson offered some insights into the processes by which heritage assessment operates in Brisbane and Queensland more generally, drawing comparisons with his home place of Sweden. He was reserved about the politics of the Lytton Road project, though he was unashamed in his critique of both developers and architects in their attitudes to built heritage. We concluded by looking at high quality renderings he produced recently from a historical recreation of the Cloudland ballroom in Fortitude Valley, a fondly remember dance hall and iconic Brisbane venue. He has created a computer model of the space as it evolved over its lifetime, based on photographs and oral and written accounts. This is going to be used later in the year as part of a musical in which artists will recreate historic performances within full-scale projections of the recreated ballroom. This resonates strongly with the emerging proposals for EBBC and I am hopeful that an admittedly busy Eriksson will become more engaged with the process.

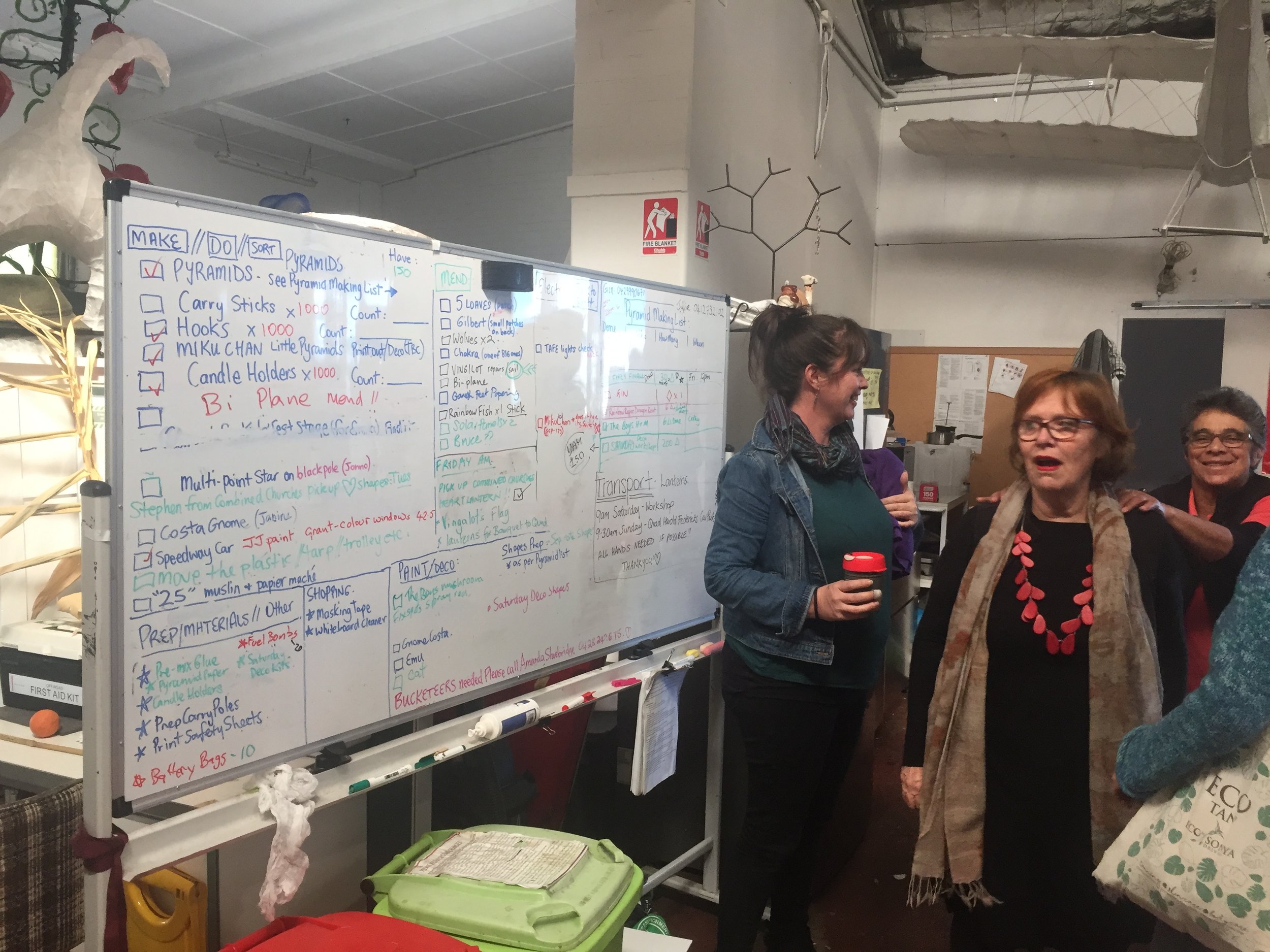

The Backbone Festival team work through the programme for the three week event. Post-its galore.

Back scratchin'

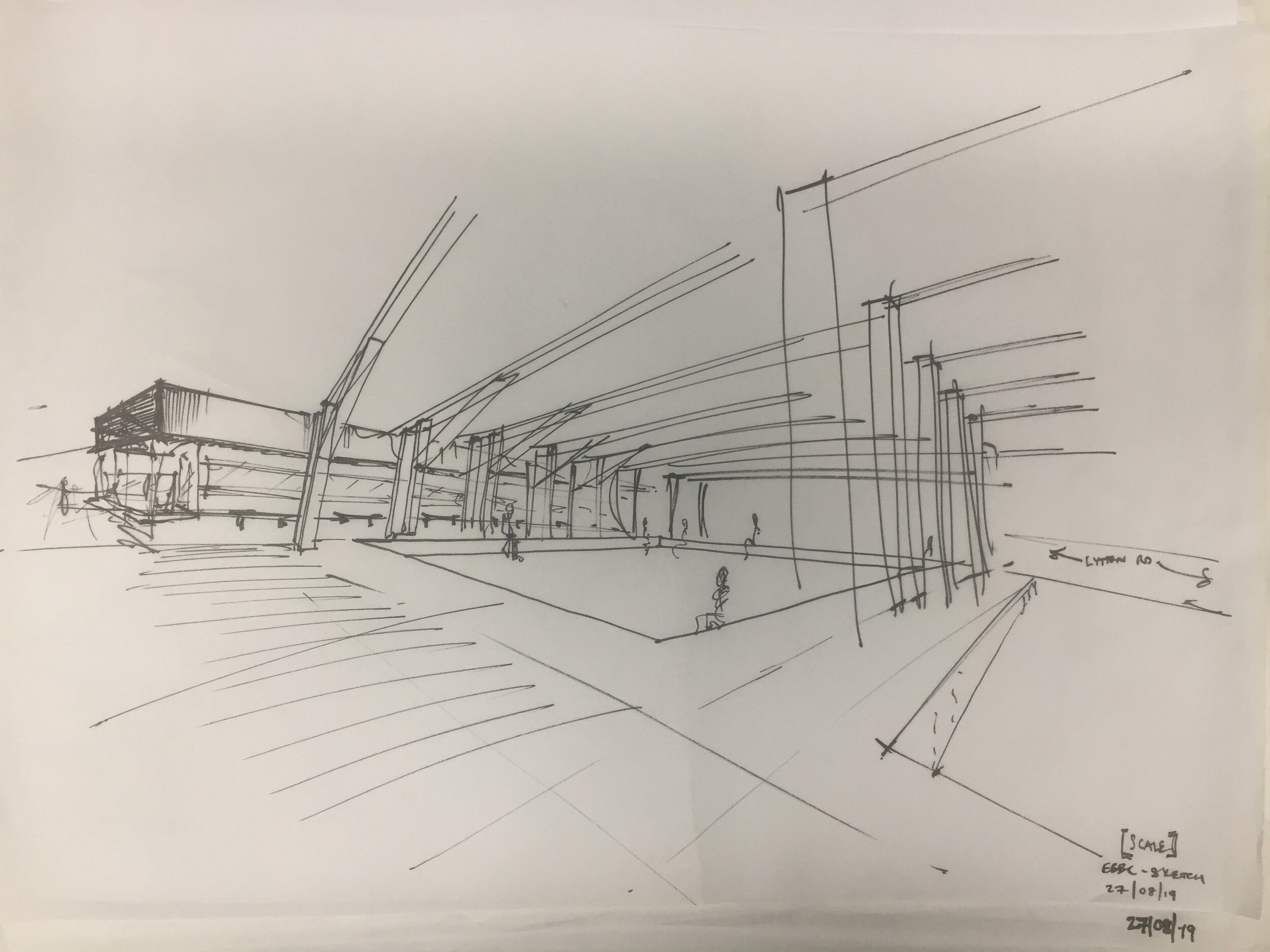

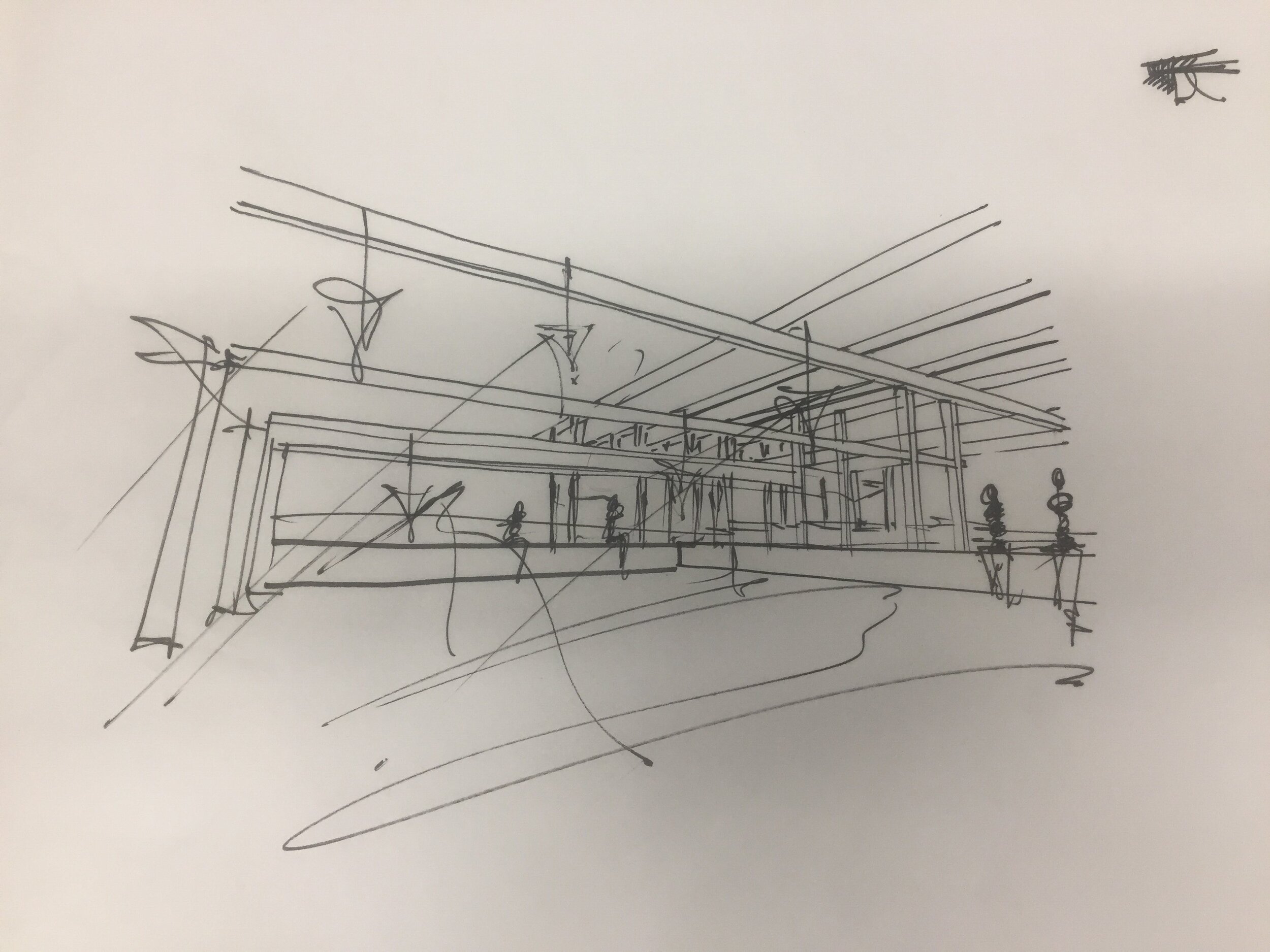

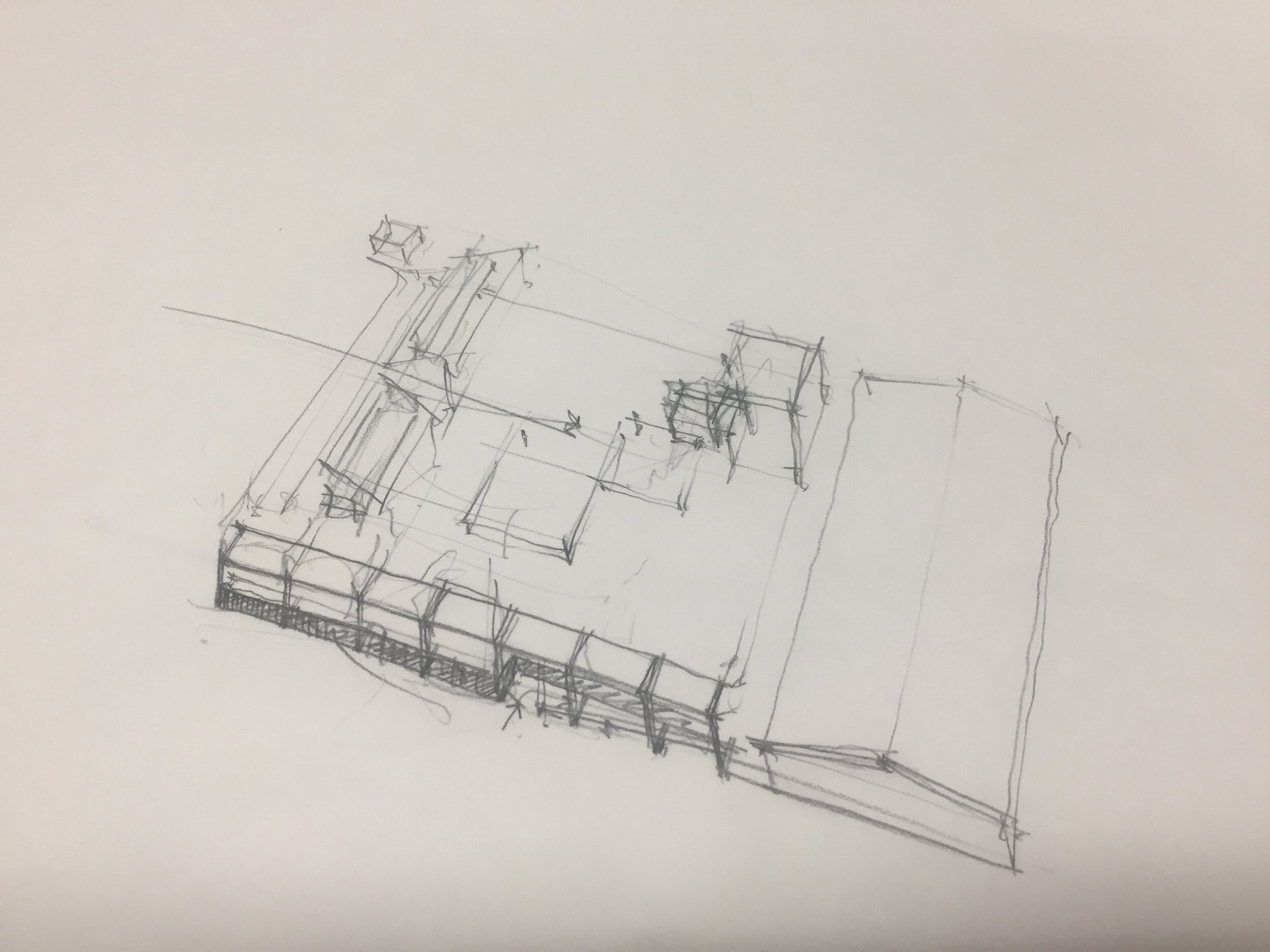

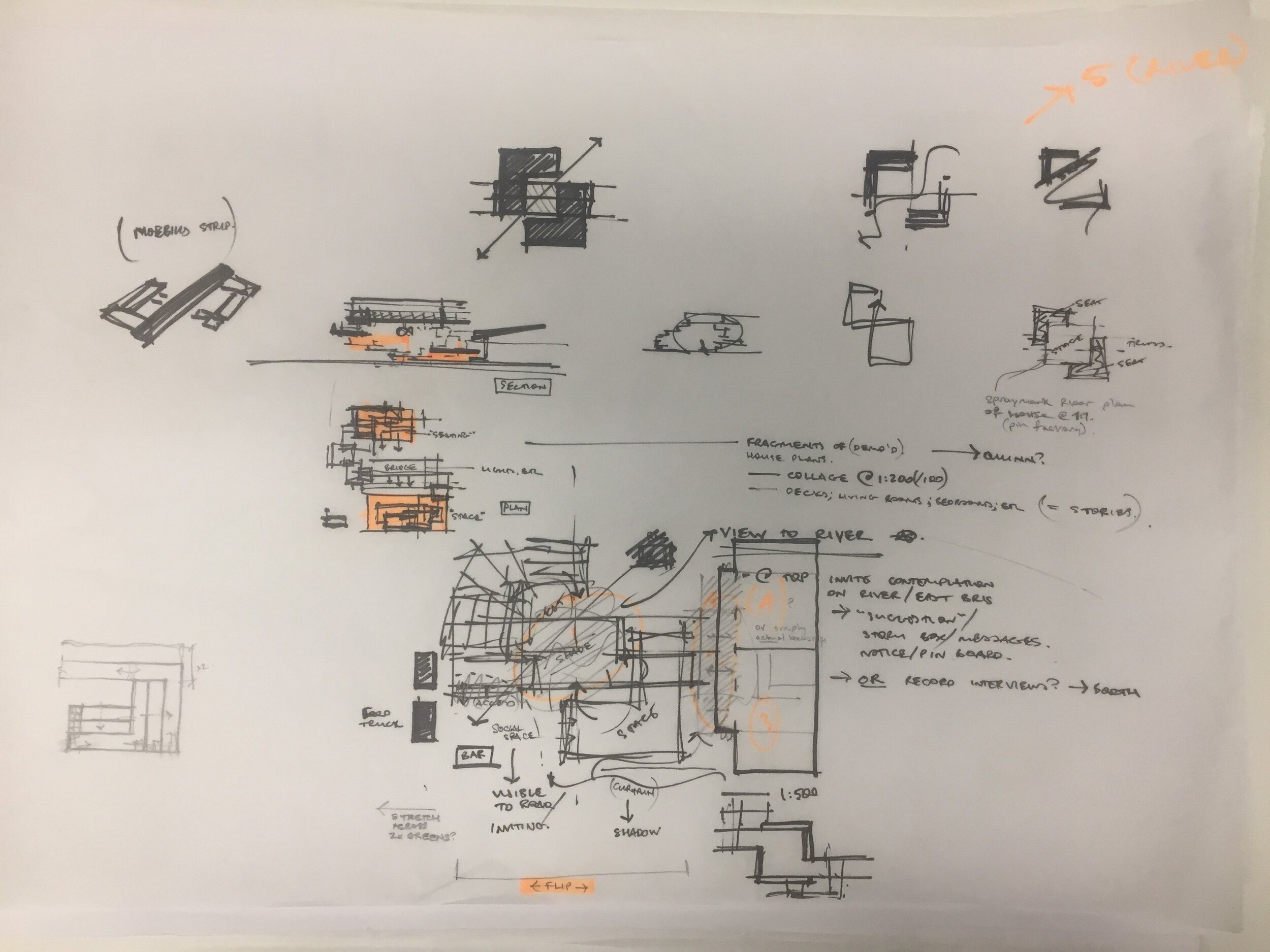

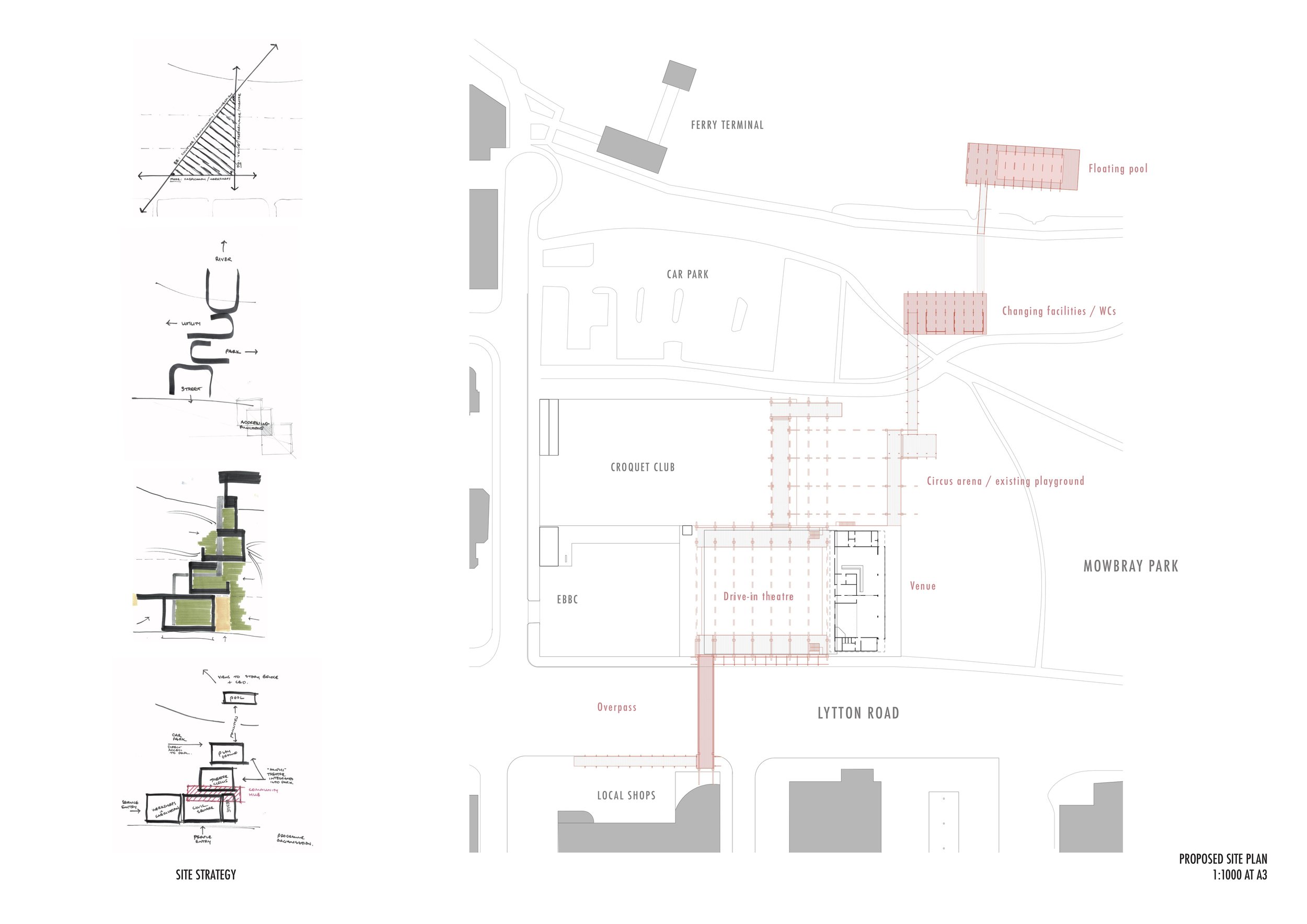

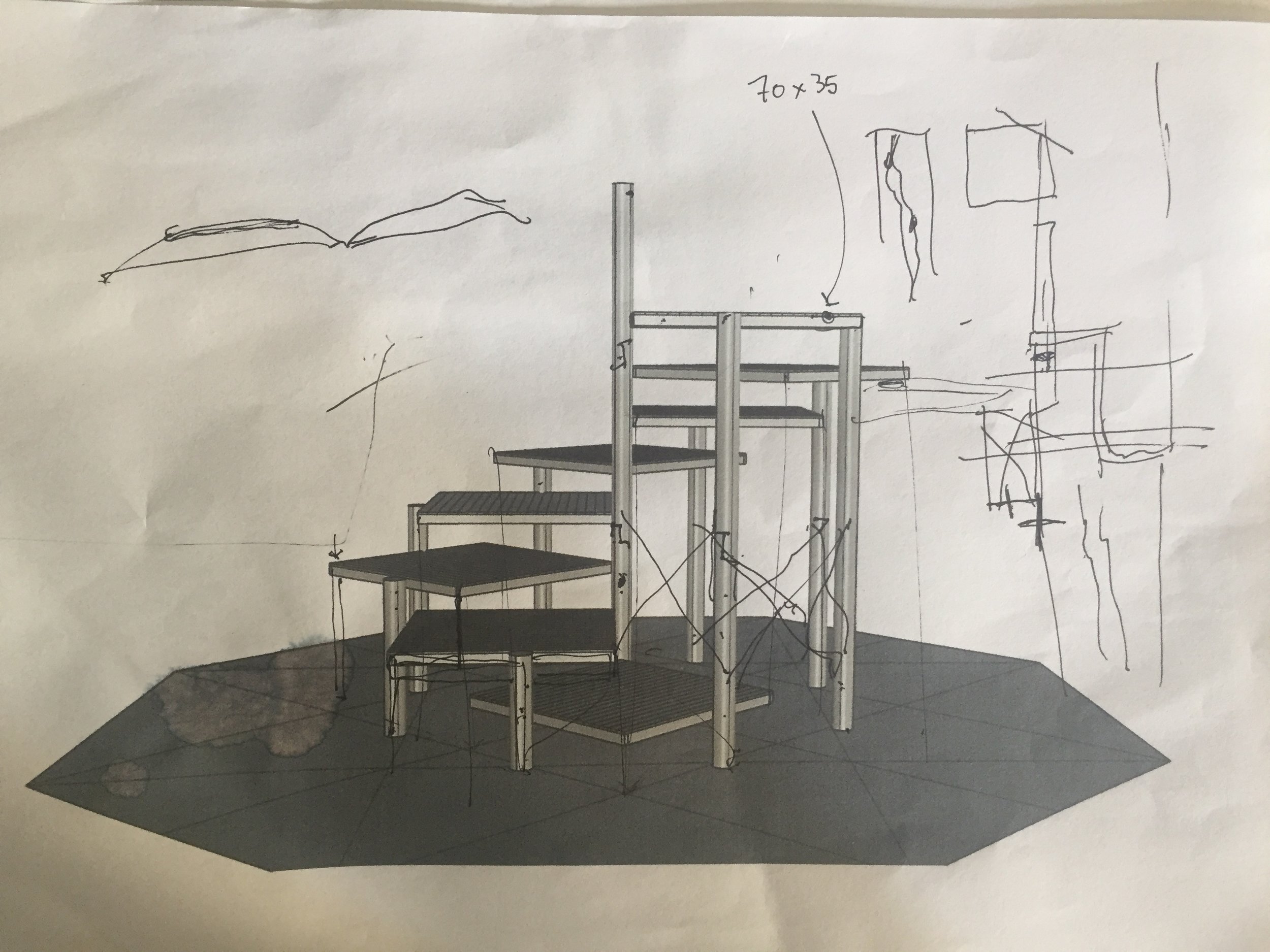

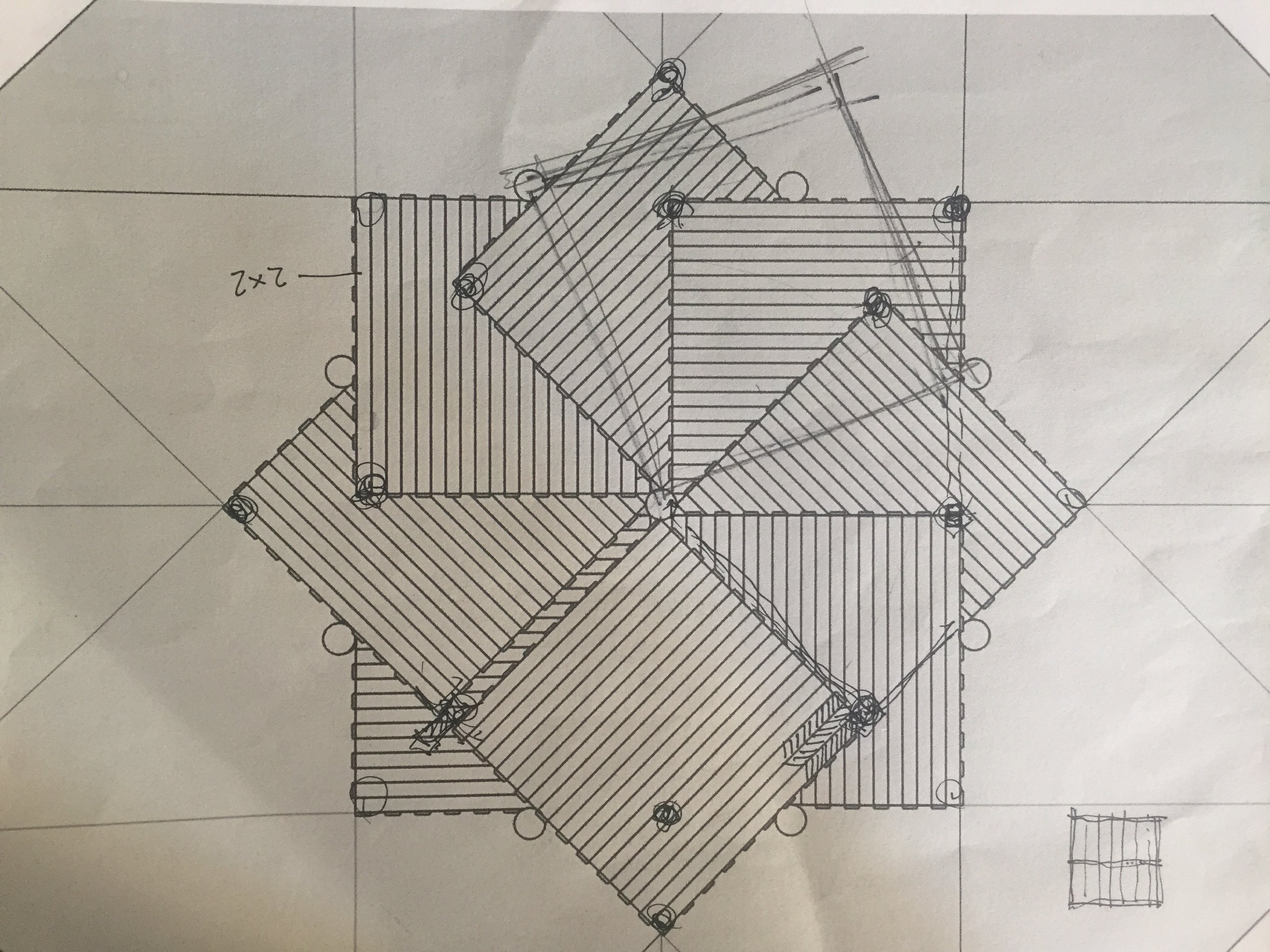

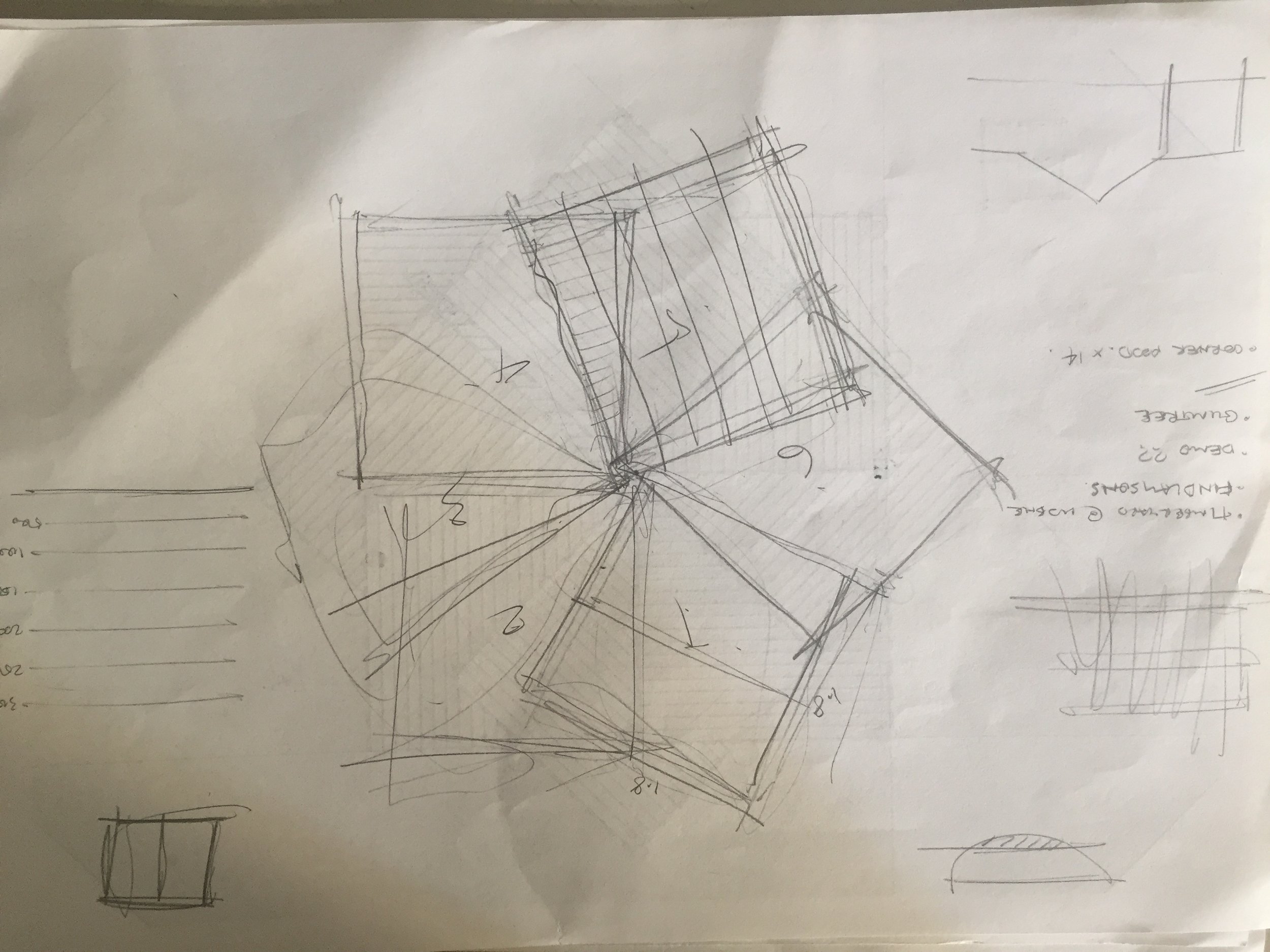

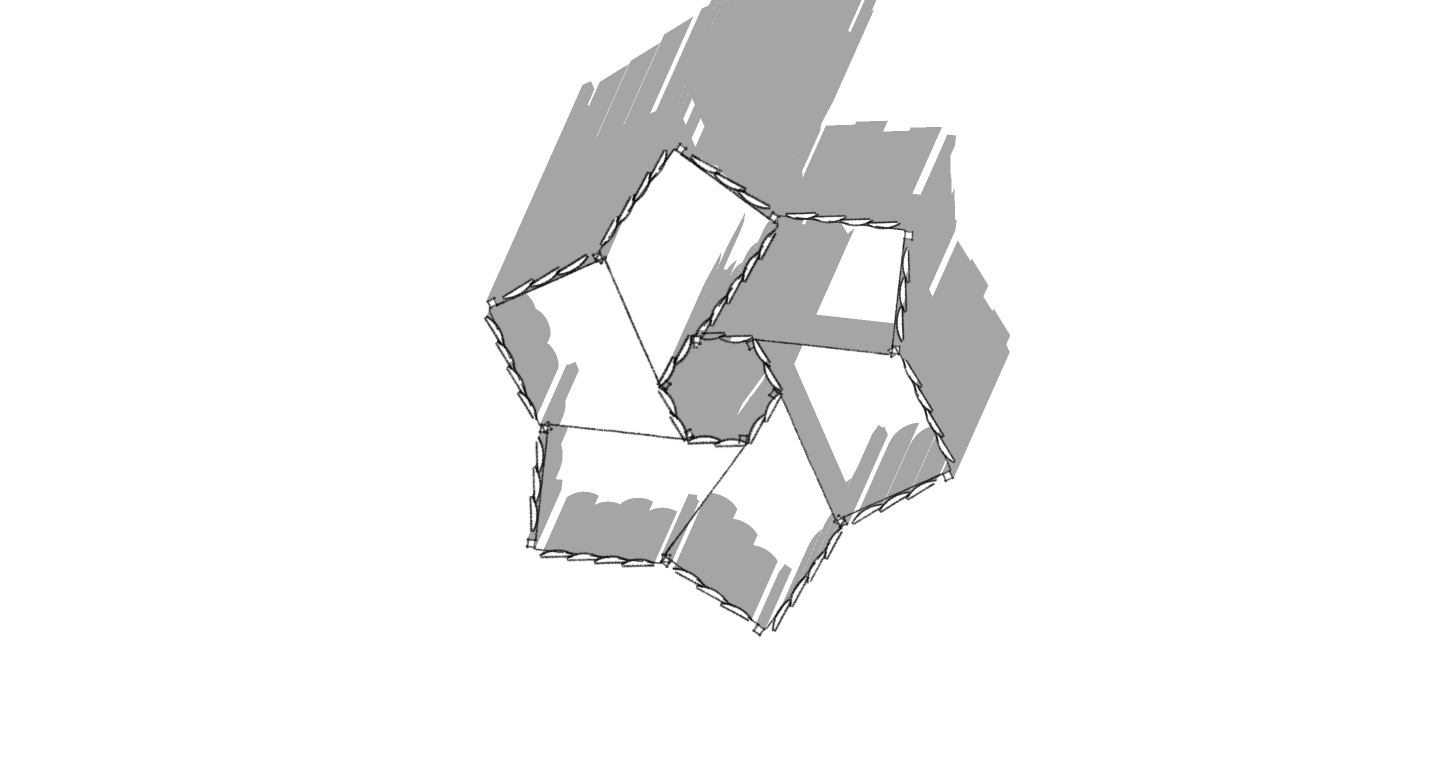

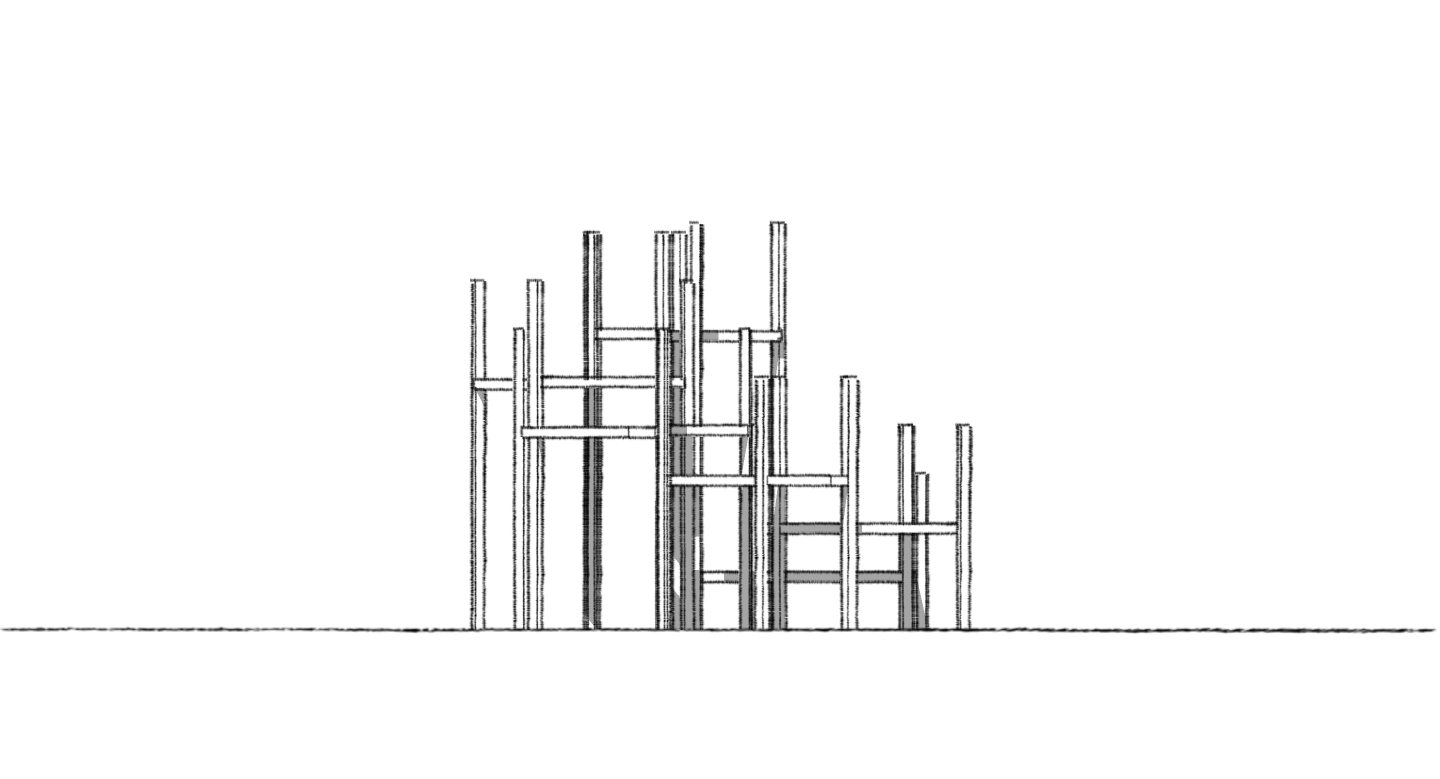

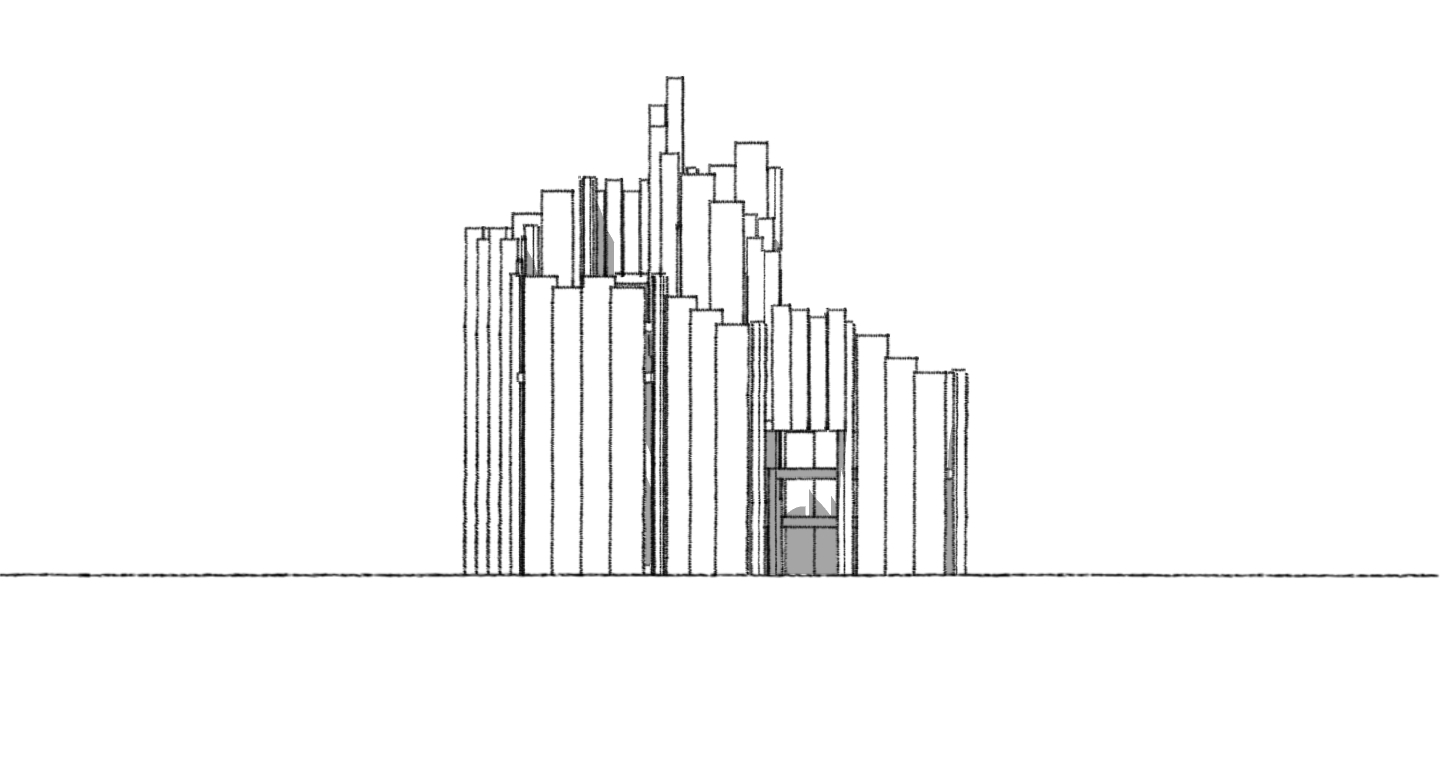

While I still grapple with documenting and analysing the Temple project, the second major ‘design test’ is proceeding a-pace. At the end of July I solicited a design brief for site design from the producers of Backbone Festival, an annual showcase of emerging theatre producers and artists held at East Brisbane Bowls Club. In mid-August I met with the festival team - a group of aspiring producers assembled specifically for the task each year (pictured above), and shared with them some of my thinking around the EBBC site - using drawings of a highly unrealistic proposal derived from the MAUD Pilot Project.

Artists are asked to respond to the festival theme of “Fake News Dumb Views”. Asking the question: ‘with media sources no one can trust and algorithms dictating our content, what can we do to cut through the white noise and better understand each other’s experiences?’, the organisers invite participants to ‘step outside the echo chamber and into each others’ living rooms.’

Since then I have been frantically trying to get a return brief and concept package together. Although, the initial hurdle of actually having a concept has been particularly challenging. Nonetheless, on Wednesday last I attempted to facilitate a design charette, inviting all of the Festival artists to contribute their ideas, needs and wants to the mix. The results remain in sketch roll format, though everyone left feeling enthused.

Backbone producers, the Festival team and artists update each other on progress.

My temporary station for the design charette with the Festival artists.

Kurilpa Derby

Last Sunday the annual Kurilpa Derby set off down Boundary Street in West End:

https://www.facebook.com/events/boundary-st-west-end-qld-4101-australia/kurilpa-derby-2019/668061670324179/

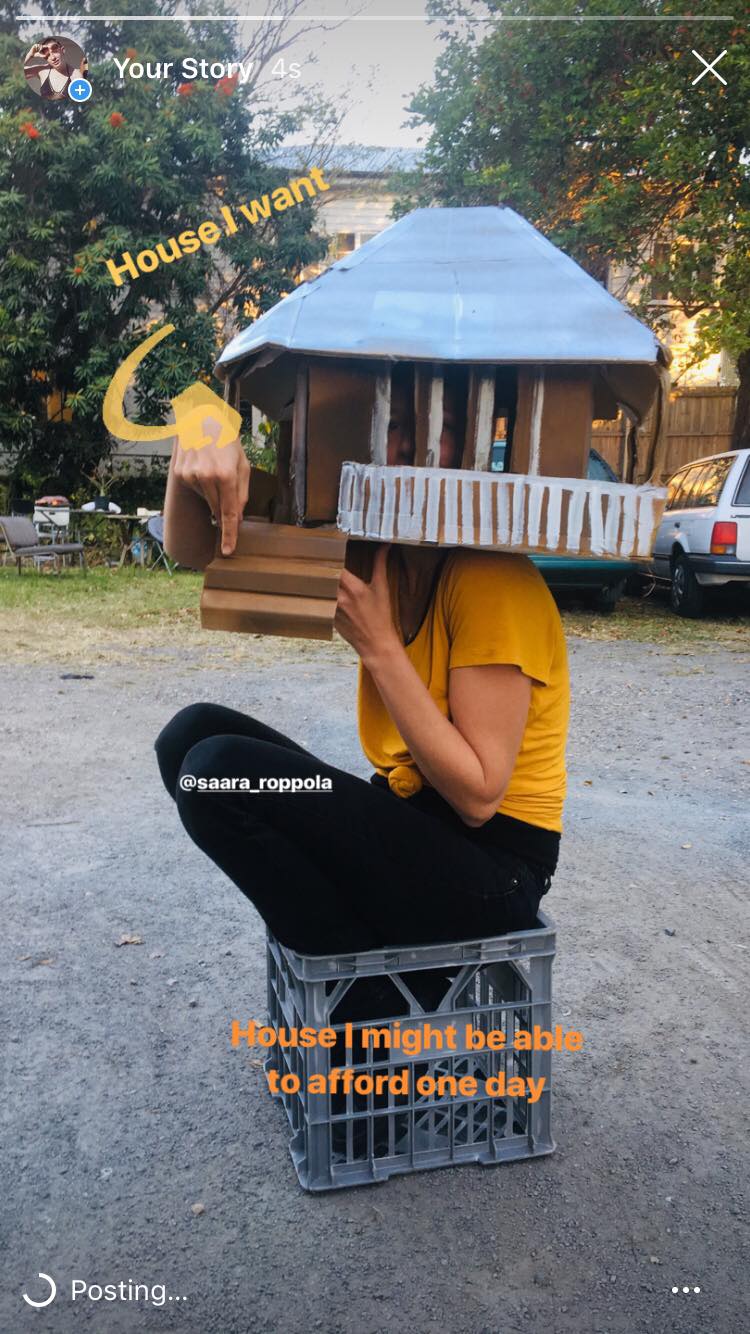

A few of the folks from Modifyre’s Rapid Art Deployment (RAD) team put together a float for the occasion - the High Rise Cult: a brand new lifestyle concept for the compact city-dweller.

Drawing inspiration from West End’s colourful, eclectic, and charming traditional houses, this stack of milk crates offers a golden opportunity for the savvy investor. But they went quick. The team of real estate agents-cum-construction managers managed to shift all the units whilst maximising spatial efficiency, by measuring up prospective buyers amongst the onlookers in street-side bars and cafés. A well-placed BURN Arts micro-grant facilitated the purchase of emergency blankets to create fresh gold flags for the occasion.

Working bees for the High Rise Cult took place over three weeks leading up to the event. Most of the work happened underneath a rented house just off Boundary Street. In typical Brisbane fashion, the space was temporarily transformed into an artisan workshop, with masters in the crafts of cardboard and masking tape, spray paint and markers, bamboo and emergency blankets, milk crates and plywood coming together to share their skills. The work often went late into the night, with meals and beers galvanising a small but dedicated community around the growing tower.

Late night work proceeds underneath 46 Russell St while dinner is prepared upstairs.

So compelling was the result of this labour - and the pitch of the sales team - that the tower was deemed by the Derby judges to be deserving of the ‘best float’ award. Lead Developer, and designer of the milk crate tower, Stirling Blacket proudly accepted the award from Councillor Matik on behalf of the team.

The irony wasn’t lost on Councillor Sri, who duly elicited a well-timed boo from the crowd. However, there doesn’t seem to have been a hint of irony for the editors of Westender magazine when they used images of the Cult to illustrate Michael Major’s step-by-step guide to place-branding…

Lead Developer Stirling receives the award for best float on behalf of the RAD team.

I eventually joined in the fun waving a gold flag atop the Wonky Queenslander - staking a claim for the weirdos…

Business as usual

Councillor Sri organised a snap protest last Wednesday in the Brisbane CBD, essentially defending the right to protest. Brisbane City Council is trying to expand laws covering the right to peaceful assembly - rights that have been hard won in Queensland, with its history of authoritarian governance and heavy-handed policing.

Students from the University of Queensland march for Civil Liberties on 8th September 1967.

In the past, traffic disruptions were often cited as a justification for withholding permission for public protests. Brisbane City Council attempted to resurrect this tactic in their challenge to Councillor Sri’s protest, although the case was thrown out by the magistrate who pointed out that free-flowing traffic is not a core constituent of democracy.

The short-notice protest came on the back of a larger Extinction Rebellion action in the city three weeks earlier, on Tuesday 6th August. On that occasion protestors occupied the street in front of the State Government offices for the morning, as part of a registered public assembly. Drawing inspiration from the global movement that originated in London, the iteration of Extinction Rebellion Brisbane is calling on the City and State governments to declare a climate emergency. More specifically, they build on the well-established ‘Stop Adani’ campaign, an ongoing anti-coal-mining campaign that aims to reverse the decision of the Queensland government to sell mining leases in the Galilee Basin - one of the world’s largest untapped coal seams. So large is the deposit in the Basin that it is estimated burning it will single-handedly release enough CO2 into the atmosphere to tip global sea temperatures beyond the +2 degrees celsius above pre-industrial levels generally regarded as the ‘point of no return’.

Needless to say, this places a fair bit of responsibility in the hands of Queensland’s ninety-three elected MPs.

The atmosphere inside the permitted area was festive, with music, art, spoken word, and food making it feel like something akin to a street party - albeit interwoven with a heavy police presence and rousing political speeches. Two sound systems provided aural stimulation - one, rather aptly mounted on a boat, was provided by the Wonky Queenslander crew, whose electronic beats kept people dancing throughout the morning despite the unseasonal heat. The other came from Councillor Sri’s office - the same used for Roving Conspiracy and other community events.

Meanwhile, in various locations around the city, outside the permitted protest area, activists engaged in more direct civil disobedience. There were 56 arrests - primarily related to traffic disruptions arising from temporary road blockades. Media presence was strong at the event - several reporters interviewed blockaders and other protesters wielding banners and signs. However, rather than asking about the nature and purpose of the protest itself, the lines of questioning were more focused on how and why people could be protesting on a Tuesday… “shouldn’t you be at work?”

This is an unfortunate symptom of Queensland’s mediocre mainstream media coverage, which tends to portray political activism as the preserve of unemployed ‘dole bludgers’, students, fanatics and extremists - certainly not ordinary respectable citizens like the reader. The shame of this reductive and often divisive approach to journalism - a profession that heralds itself as a pillar of liberal democracy - is that it discourages active participation in political life and ultimately glosses over issues of government accountability.

In any case, by 2 o’clock the music had stopped, the protesters had packed up and the road had re-opened. Government workers went for a late lunch. The police filed out reports. The fanatics went back to the drawing board. Business as usual.

The author inspecting the night’s progress before packing up for the night.

A shot in the dark

It’s a truly DIY affair out on the paddock. Unlike commercial construction projects, the meagre event budget doesn’t extend to lifting equipment or lighting towers. Thankfully, there was one leftover length of 2”x4”, just enough to knock up this makeshift tower.

The unpredictable and slow affair that is building large artworks, particularly in isolated locations, often requires crews to work from early in the morning until late at night. Without sophisticated lighting and power arrangements however, this can be a serious challenge. In order to dissuade Leo from relying on night work as the event drew nearer and the pressure mounted, we decided to go out and work under lights for a short while on Saturday night, just to give everyone a feel for how challenging it can be.

Before dusk, we set up a makeshift lighting tower (pictured above) and tidied all the tools, consumables and other equipment back under the marquee and secured anything that might blow away should the wind pick up - rule number one of working in the dark (or in the daylight I suppose) is to know where the hell your tools are! Otherwise, very little will get done.

After dinner we loaded the trailer up with firewood, snacks, and a good playlist and headed back out to site. I offered a brief safety pep talk, just reminding everyone to be extra vigilant, and to call it when they were too tired. It was agreed that we would only work around the ground for tonight - there was no rush, and there was plenty to be done down low in any case.

The exercise more or less had the desired effect - Leo agreed that night work is a pain in the ass. However, by Tuesday, the urgency of finishing things off before gates opened superseded the hassle and the work went late into the night…

Printed drawings, a whiteboard, and lots of gaffer tape - oft-overlooked essentials for any successful build

Stairway to heaven

A more secure marquee, music to drown out the generator, and kangaroo bones to ward off the westerlies.

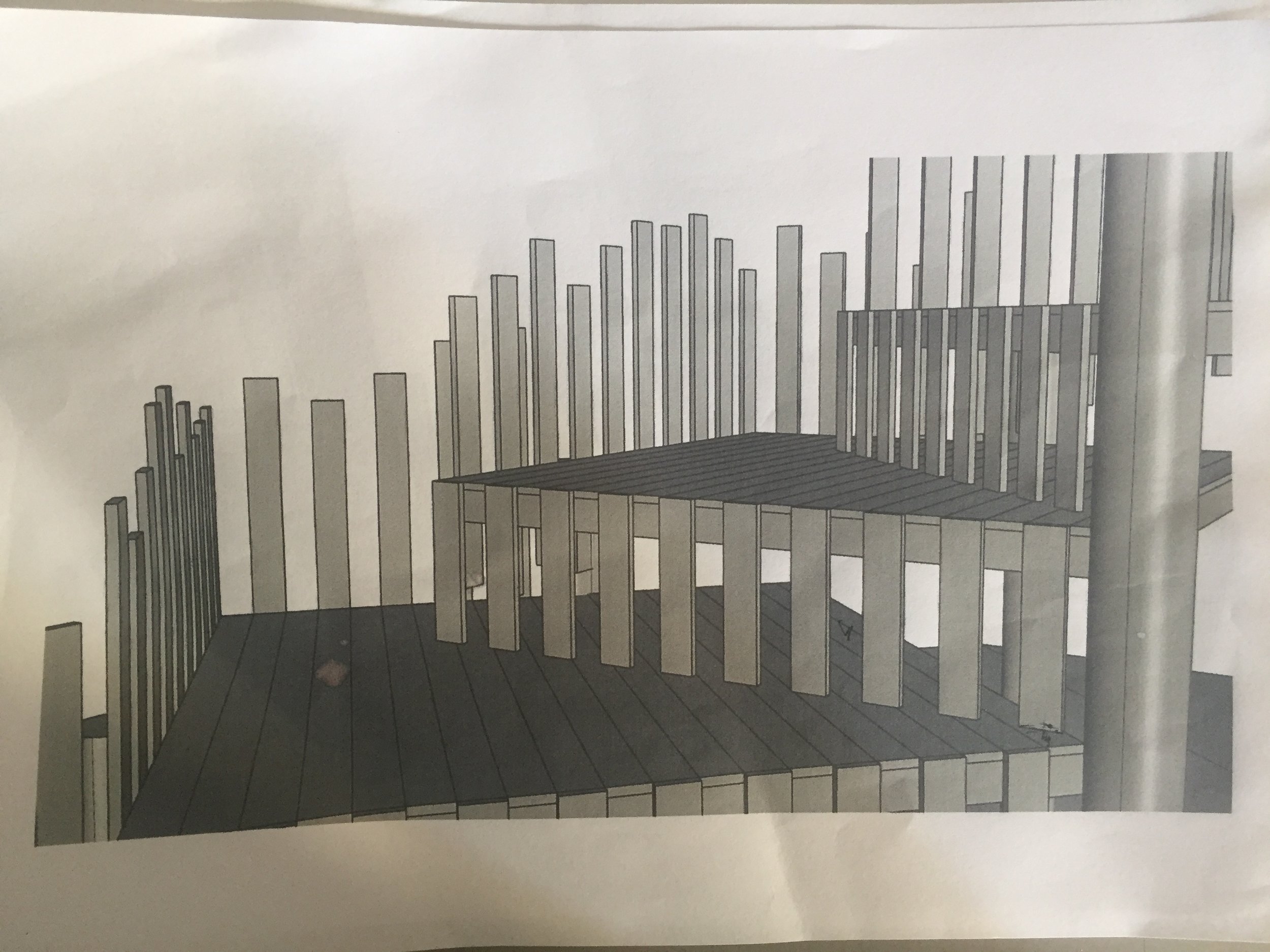

29 June: Once the initial hurdles were overcome, things proceeded apace. A fresh marquee was erected and a functioning workspace duly arranged, complete with whiteboard and printed construction drawings for the crew to consult.

By dusk on Friday we had progressed from just one platform to four. Along the way, some quick decisions were made regarding bracing and ballustrades to keep the crew safe as the structure grew skyward.

9am: Jorja and Maneh work on the first platform while James, Ruth and Micalah prep the second.

10am: Jorja levels platform two. Behind, number three lies on its side, assembled and ready to be placed.

12pm: James begins work on the ballustrades - Maneh suggests it might be easier to figure out after a bite of lunch

2pm: After lunch, things were much clearer - the ballustrades went up parallel and the architects were happy.

5pm: James gathers the last of the tools. Four platforms up, just two to go.

The ‘original’ Temple crew, from left to right: Ruth Buckley (Brisbane) and Michalah McCulloch (Brisbane), two first-time volunteers with no previous build experience; Manuela Buenavida (Brisbane / Peru), the event’s Leave No Trace (LNT) coordinator; Leonor Gausachs (Brisbane / Chile), architectural graduate and Project Lead; James Hastings (Perth), a plumber and all-round construction machine; and Jorja Christensen (Perth), a highly experienced set designer, builder, and self-declared carnie. Over the course of the next week the project would come to involve over twenty people, with volunteers coming and going throughout the different stages. Leo discovered that her role as Project Lead was as much about building sound human relationships as about building sound structures.

One step forward two steps back

At dusk on Tuesday 25th I arrived in a rented Pantech 3-tonne truck with a consignment of flat-packed materials for the Temple and the Bug. We unloaded on Wednesday and got off to a promising start, organising materials and setting up the build sites. However, it proved to be a false start when our temporary shade structure succumbed to high winds. So, construction finally got underway on Thursday, with the assembly of the first platform and the marking out of the overall geometry at 1:1.

27 June: The hardwood posts for the first platform were dug into the ground. The team were then reminded that our permit from QPWS includes a condition that no holes be dug in the paddock, in order to protect the already fragile pasture from significant damage and degradation. The platform was removed and the holes filled back in - a different strategy would be needed to stabilise the structure.

I spent the day offsite in Inglewood, re-establishing our presence with local business owners and wrangling up various necessities - showers for the crew at a local motel, advance notice to the pub that there would be twelve hungry workers coming in for dinner on Saturday evening, ice-creams from the supermarket. In a regional community like Inglewood, suffering the effects of drought and depression, it is important that Modifyre be seen to bring with it some benefit to the place. This doesn’t just mean spending a few dollars around town - although that is important too - but that we make the effort to foster positive relationships with local people across the board.

Most important to the build was a visit to Ken Reilly, the “Ironbark Executioner”, at his hardwood mill a few kilometres outside town to the southeast. In exchange for a carton of Great Northern beer, Ken let us loose in the paddock at the back of his property where he disposes of flitches - the unusable bark offcuts left over in the sawing process. We arranged for a local contractor, Red Rock Transport, to deliver two loads of flitches from Ken’s place to Yelarbon State Forest the following day, to be used primarily as cladding material for both the Temple and the Bug (though they proved useful for a wide variety of other things - including a mantlepiece and decorative fascia in the increasingly sophisticated crew bar).

28 June: The following morning Red Rock duly delivered the first load of flitches. There was some dispute amongst the crew as to whether the tip truck was sufficiently loaded to justify the $100/hr commercial rate that we were paying. I explained somewhat matter-of-factly that Modifyre is run by a non-profit entity (BURN Arts, Inc) with extremely limited resources, but that we were striving to make a positive contribution to Inglewood. My frustration wasn’t well received. However, after the second delivery arrived, Tom ‘Bundy’ Hamlyn, the DIC Head, told me that Red had decided to waive the fee altogether. It isn’t clear what brought about the change of heart, though I suspect perhaps there was another case of beer involved…

Jorja and James look on as local contractor Red Rock makes the first delivery of Ironbark flitches from Ken Reilly’s hardwood mill.

Background: The pile of flitches at the Temple site ready to be sorted. Ironbark is so-called for a reason - each length of bark is a two person lift

Foreground: the mangled shade structure that succumbed to high winds the previous day, soon to be carted off to the local tip.

Building the infrastructure to build a structure

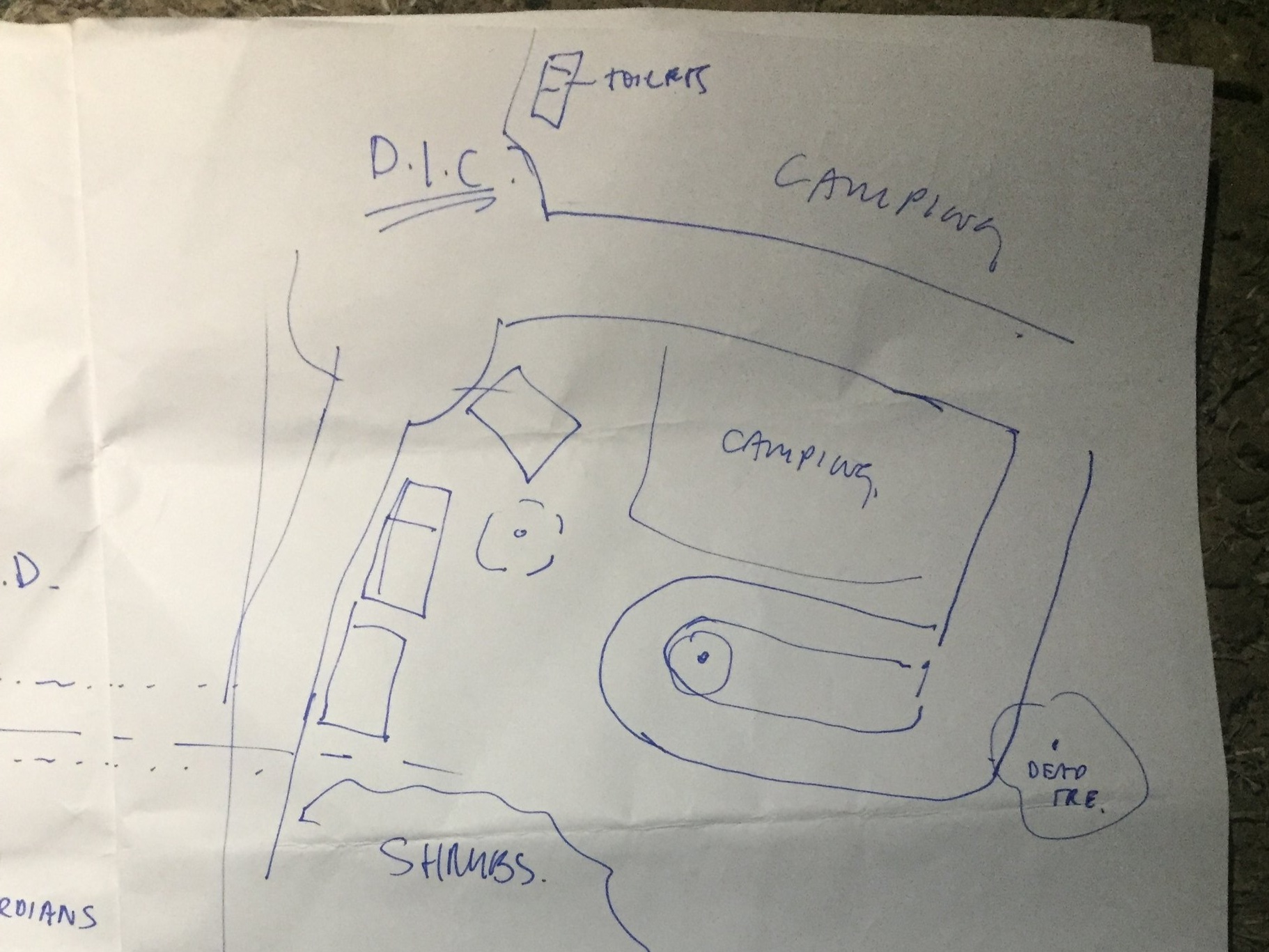

The first few days onsite at Yelarbon were spent unloading and constructing the basic infrastructure to allow the larger builds to proceed. This included the crew kitchen, workshop and storage areas; marking out the main access routes and camping areas; shade structures at the build locations, and of course a portaloo - though in previous years this has only arrived after a few days onsite, so to have it from the beginning was considered something of a luxury! Next up was power and lighting, a site office, and a dining space.

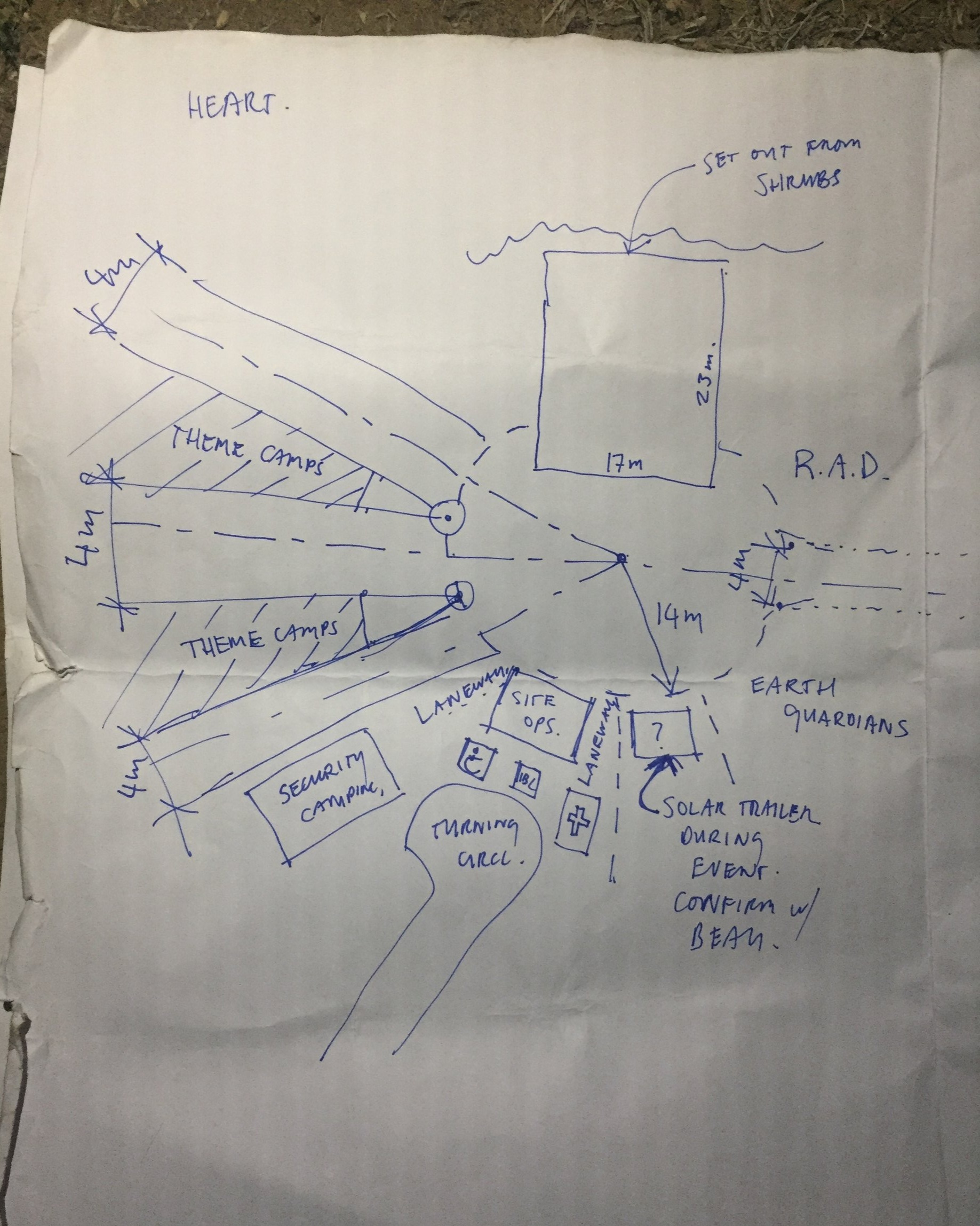

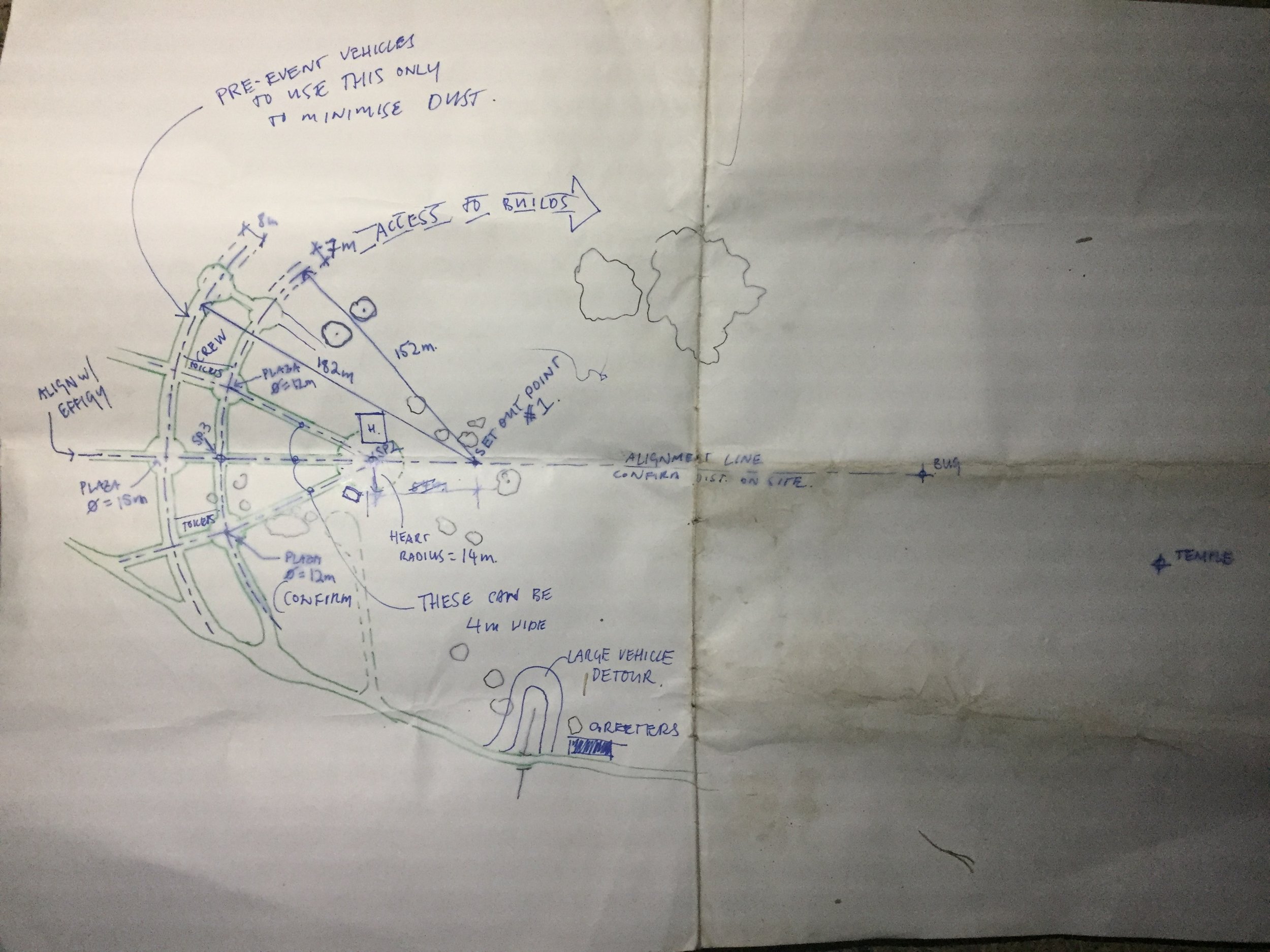

The event site was marked out using a laser measure from a fixed set-out point indicated on the hand-drawn site plans shown below. These plans were then used by the Dept of Infrastructure and Construction (DIC) to lay out the key infrastructure starting with the crew compound and working outwards. Drawn by the event Town Planner and architectural graduate Stirling Blacket, the site layout was established through a community design process over the course of several months leading up to the event. The key considerations were local Indigenous land use and mythology, soil conditions, existing burn scars from previous year’s events, traffic management and minimising vehicle impact, noise mitigation for neighbouring graziers, and the creation of effective civic spaces.

25 June: The first structure goes up on site - a 12x8m marquee, soon to become the crew kitchen, tool storage and workshop.

26 June: shade structures are erected at the build sites, some 500m from the crew compound, affording the Temple and Bug crews (and their tools!) some protection from the elements - primarily sun and dust - in the days ahead.

The author (left) giving Tom Brown (middle), effigy lead, a hand getting some additional shade up in the wind, while Jorja Christensen - a blow-in from Perth - gets the tool table set up for the day.

It’s a long walk back to camp if you’ve forgotten your tool bag - the view back towards the crew compound from the Effigy site (300m away). Keeping builds on schedule is an ongoing challenge - a couple of forgetful moments due to dehydration and fatigue and the short Winter days can very easily slip away.

Winter warm up

Over a month since returning from site, I am finally finding the energy to pick up the pieces from the Temple project. Despite having undertaken many such projects in the past, the physical, mental and emotional exhaustion post-event still took me by surprise. After three weeks living and working in our temporary encampment in Yelarbon State Forest, inhaling dust and sleeping on a drought-stricken winter paddock, it was perhaps predictable that I would be an easy target for the ‘Ekka Flu’.

This week in Brisbane is the Royal Exhibition - better known as ‘The Ekka’ - an event that brings visitors from all over the state, along with particularly bitter westerly winds and an invasion of fresh microbes. Shortly after giving a Friday afternoon presentation on the Temple project at m3 architecture, a design practice based in Red Hill, I fell ill and spent a week staring at the ceiling of our rented accommodation, unable to get out of bed.

In any case, I am more or less recovered now and playing some serious catchup on fieldwork and documentation. In the following posts I will try to quickly summarise the activity of the previous few weeks.

First up - it’s time for the build crew’s morning stretches:

IMAGES: Modifyre veteran, former Temple and FLAME (fire safety) lead, and Kung Fu enthusiast Andy Price helps the crew to warm up on the first morning of the build.

IMAGE: Eve Jeffery @ Tree Faerie Fotos

Co-creating ritual: Lismore Lantern Parade

I recently visited the town of Lismore in northern New South Wales, to participate in the annual Lantern Parade which takes place there around the winter solstice.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=27&v=SXi-R1x1S34

The following is a belated account of the trip.

LISMORE

Lismore is one of the main urban centres in Northern Rivers, a coastal region stretching from Tweed Heads and the Border Ranges in the north, to the Clarence River in the south. With its fertile flood plains, lush subtropical rainforest and abundant marine life, the economy of Northern Rivers is founded on agriculture, forestry, fishing, and tourism.

Since the early 1970s the region has also been known as a hub of Australia’s counter-cultural movements, an equivalent perhaps to the hippie movements of the United States. The Aquarius Festival, which took place in 1973 near the small farming community of Nimbin, is often regarded as ‘Australia’s Woodstock’, and is credited with having galvanised the many alternative communities that still characterise the area.

In this regard, Northern Rivers is a kind of mirror image of northern California, with its particular confluence of social, political, and economic factors: resource-based wealth and niche high-quality agricultural produce, self-protective farming communities and strong narratives of pioneering settlement, back-to-the-land social and environmental movements, green and anarchist politics, a strong dose of surf culture and a scepticism of government. Lismore encapsulates this blend - a dairy farming town with a radical environmentalist Deputy Mayor; an electorate spilt between the conservative Liberal National Party and the progressive Green Party; the seat of a Catholic Bishop, with a solstice ritual at the heart of its contemporary identity…

The new Lismore Regional Gallery, part of the town’s civic centre Quadrangle alongside the Town Hall and Library.

LANTERN PARADE

The Lantern Parade is an annual community event held around the winter solstice. For one night, Lismore is transformed into a wonderland, as hundreds of LED paper & bamboo lanterns of all shapes and sizes are paraded through the streets. As a ritual, the event reconstitutes and reconfigures the economy of the town - the quintessential fête. Everyone is involved in some aspect: emergency services dedicate their resources to escorting the parade and safely burning large structures in the civic quadrangle, local suppliers and service-providers are engaged to provide infrastructure and labour, vendors set up along the streets and local businesses place lanterns in their windows, schools and youth groups from across the region make lanterns, masks and costumes to represent their communities, the local Council provides administrative support, work-for-the-dole and TAFE students undertake work experience placements.

There is no part of the local community untouched by the event. Community workshops start at Easter each year with many other volunteers travelling from across the Northern Rivers region, South East Queensland, around NSW, South Australia and Victoria to participate. The event attracts approximately 25,000 people each year and is estimated to contribute $3.4 million to the local economy. With this social, economic and cultural contribution to the City, the event has been formally recognised by Lismore City Council as its signature event. In 2019 the event celebrated its 25th anniversary to the theme ‘Rivers of Light’, representing all the community events that the Lantern Parade has travelled to over the years.

INFRASTRUCTURE: THE LANTERN SHED

Amy and I drove to Lismore on Friday 21st June, a two-hour drive south of Brisbane across the Qld-NSW border in a borrowed Subaru Forester. After dropping our bags at a friend’s house on Wotherspoon St (in which, we would soon discover, virtually everyone we spoke with seems to have lived at some point), we headed straight over to the ‘Lantern Shed’ on Keen Street, headquarters of Light’n’Up, the company responsible for instigating the Lismore Lantern Parade. An independent community arts organisation, Light’n’Up is perennially under-funded and under-resourced. They rely entirely on the energy and goodwill of volunteers to produce an event of incredible scope and quality.

It wasn’t long before we were put to work. After a few quick introductions we found ourselves packing a truck full of large paper and bamboo lanterns, ready to be sent across to the Town Hall. This is a typical experience of the Lantern Parade - people travel from all over the region and indeed the country, by whatever means they can muster, to give their time to the lantern parade. They are generously hosted by the community in Lismore, who in turn dedicate their own resources to transforming the town into a light-filled wonderland for one night.

We managed to squeeze in a hello with Jyllie Jackson, the legendary founder of Light’n’Up, in between phone calls and relentless questions from her army of volunteers. Jyllie’s determined vision has driven the Lantern Parade project for over 25 years and been the inspiration for many imitators. She showed us photographs of some of her crew parading lanterns through the wards of the local hospital on the previous evening. Her favourite quote from a patient and long-term Lismore resident: “it’s the best medicine”.

I mentioned the idea of trying to describe the ‘infrastructure’ of a ritual like the Lantern Parade to Jyllie - her response: “Our infrastructure is Madness.”

Jyllie busy at her desk - fielding phone calls, filling out insurance forms, answering questions, and putting the finishing touches on her cat lantern!

RITUAL: FIREY FINALE

After doing a few truck loads between the Lantern Shed and the Town Hall / civic centre, where much of the weekend activity is concentrated, we were sent off to help out with the fire crew. These folks put together the finale, which takes place once the Lantern Parade has arrived at the end of its route at the civic centre. It involves an elaborate sequence of performances involving various kinds of fire props, flares, etc, and culminates with the burning of a ‘main image’ and fireworks display.

The tools and materials required to pull off this spectacle are fairly simple, but impressive nonetheless - lots of hessian, chicken wire, bamboo & hardwood stakes, black gaffer, plastic sheeting, and of course lots of firelight fuel.

Temple Project - Workshop #2

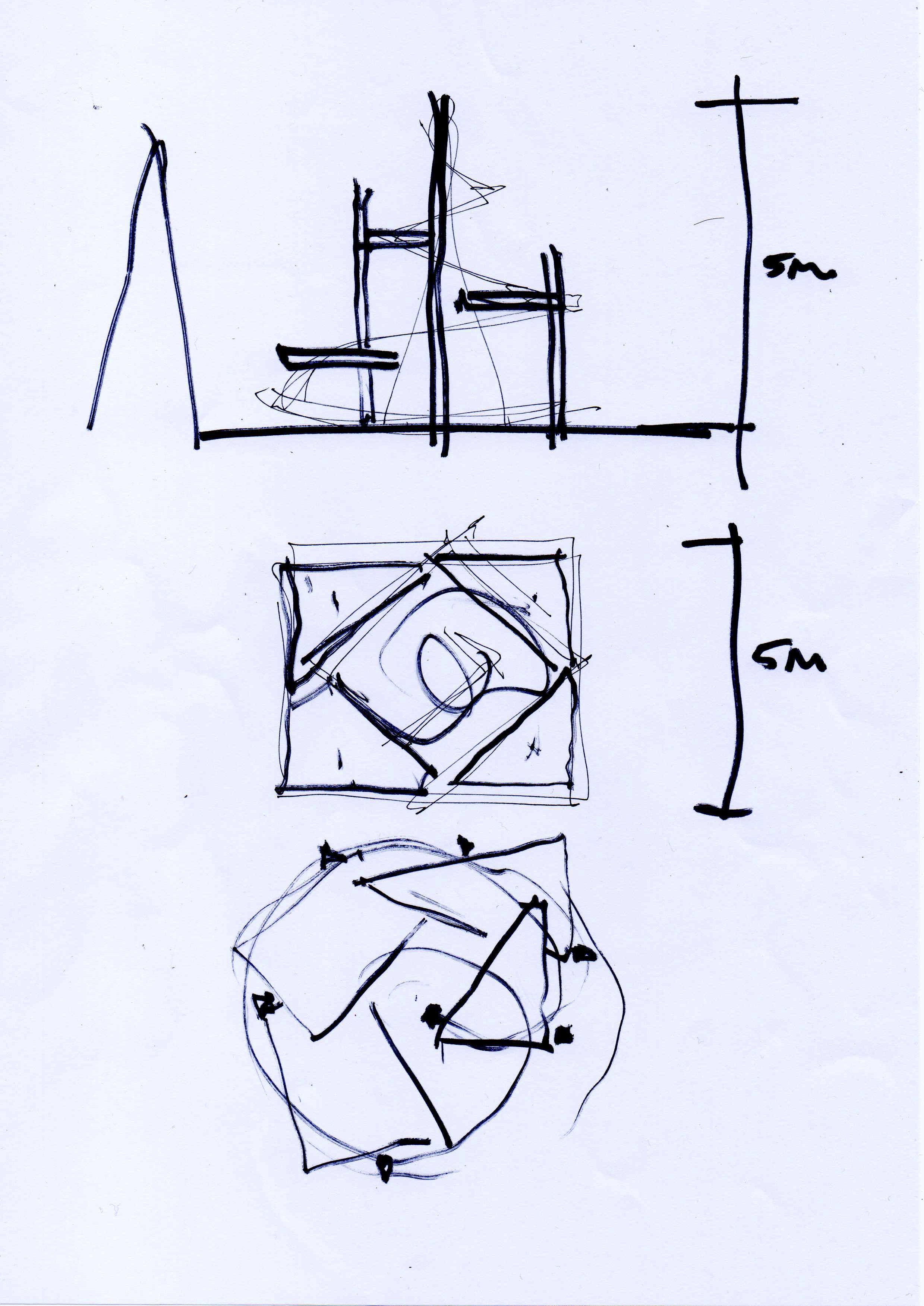

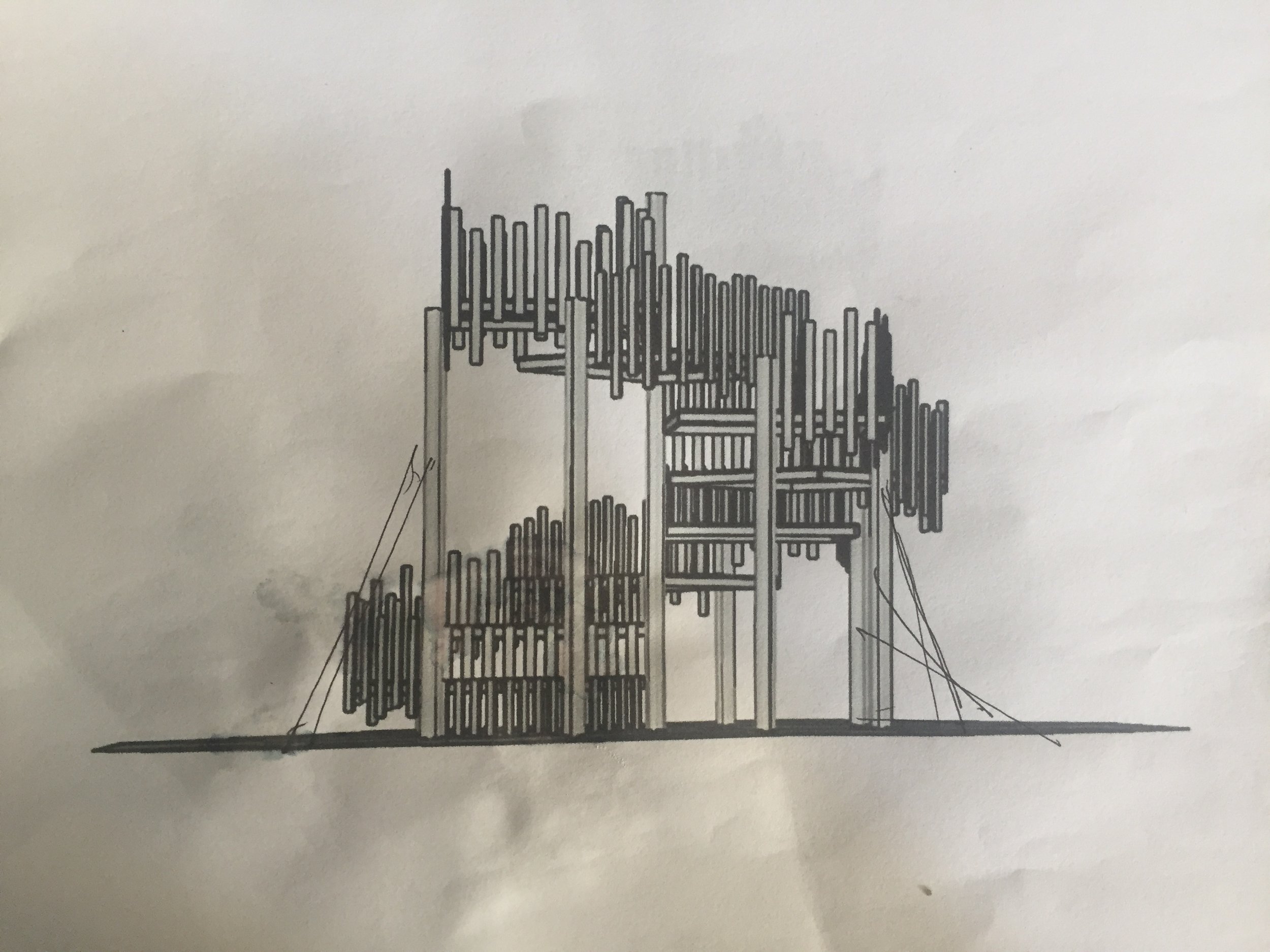

This weekend the Temple project continued apace, with the design process quickly morphing into a 1:1 modelling exercise. I say modelling because we erected a structure of 6m in one afternoon as “proof of concept”, only to dismantle it again the following afternoon during a typically sudden and absurdly heavy Queensland rainstorm.

A stack of Aussie hardwoods - a bit of work to de-nail, but otherwise in good condition.

FRIDAY:

In between conference sessions, much of the day was spent on the phone to timber suppliers and scrap dealers trying to source suitable framing timber for the main structure. I put together a quick concept ‘pitch’ document to send out to various potential donors.

We eventually located a selection of recycled hardwoods underneath the house of an event attendee - perfect for the superstructure - but had to settle for a purchase of pine for the platform cassettes.

SATURDAY:

We quickly fabricated the deck framing - and tested the set up by putting them together. It was encouraging to see the structure remain standing under the weight of several grown men, particularly given that our volunteer insurance didn’t cover them on a temporary structure not built to code.

SUNDAY:

Started putting down decking on the floor cassettes before disassembling the structure in order to prepare for flatpack and transport. The day was cut short by a rainstorm that left the crew soaked - although it was probably the most efficient team work I’ve seen from them to date!

MONDAY:

Met with the RAD team - performance, sound, lighting and fire - to discuss plans for the burn ceremony. We used plans to draw out possible approaches to coordinating various proposed elements including instrumental performance, crowd singing / humming, smoke emitters, costumes, and the strategy for lighting the piece. Often people who have lost loved ones in the last year are invited to light the structure.

Afterwards I headed back over to EBBC to look through the shed there and retrieve some of my old hand tools and ended spending an hour sorting through a box of assorted fixings - we shouldn’t have to purchase any more for the project I reckon.

Options for cladding patterns & materials.

TUESDAY (today):

We finished decking four of the six cassettes - the remaining two will be done in-situ, as they are too heavy to manoeuvre into place without heavy lifting equipment.

Meanwhile, the design itself continues to develop and be refined as the build progresses. Discussion moved today onto cladding materials and patterns. We confirmed collection of flitches (bark offcuts - mill waste material) with the local hardwood mill in Inglewood (for the price of a carton of beer) next week. At the same time, we are discussing strategies for safely burning the structure so that it falls in a predictable way - an interesting fire engineering experiment.

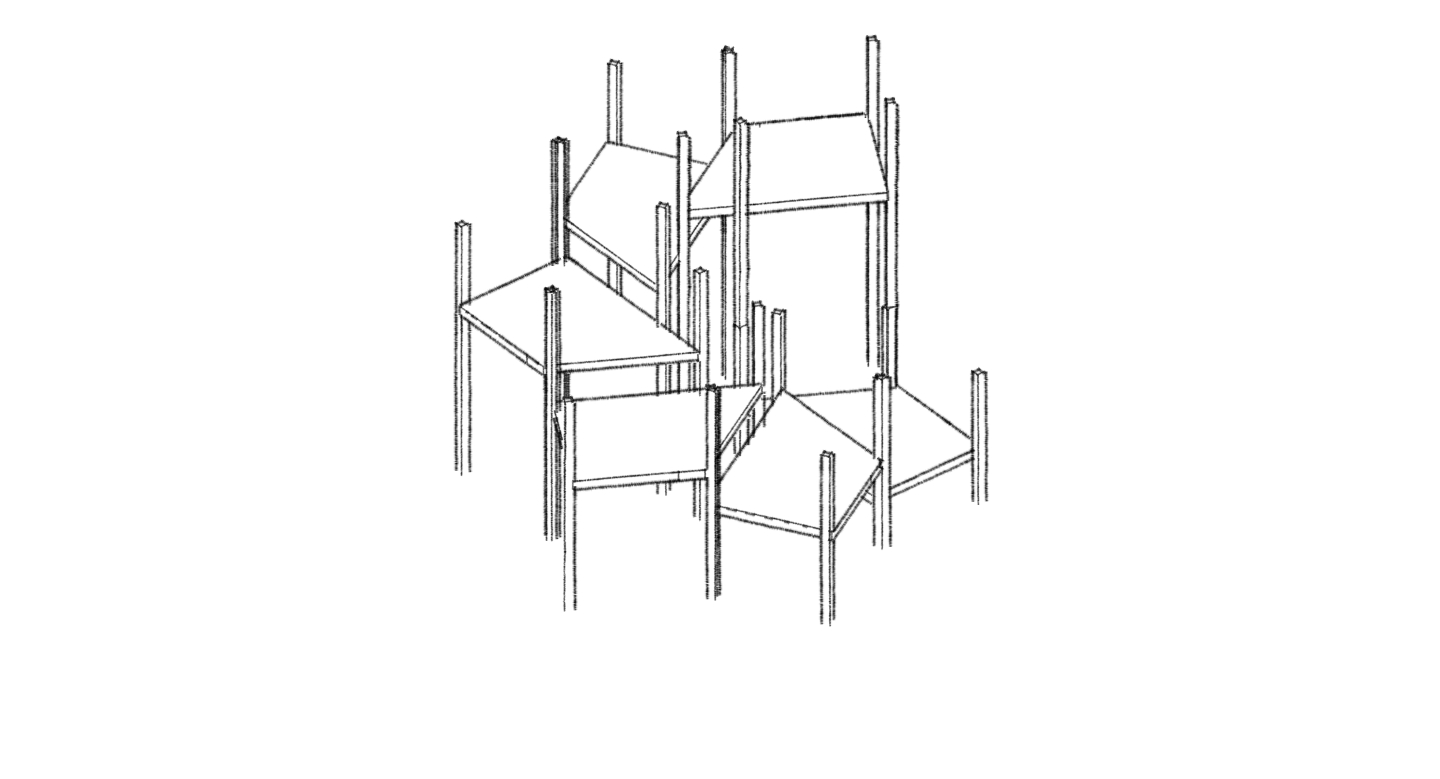

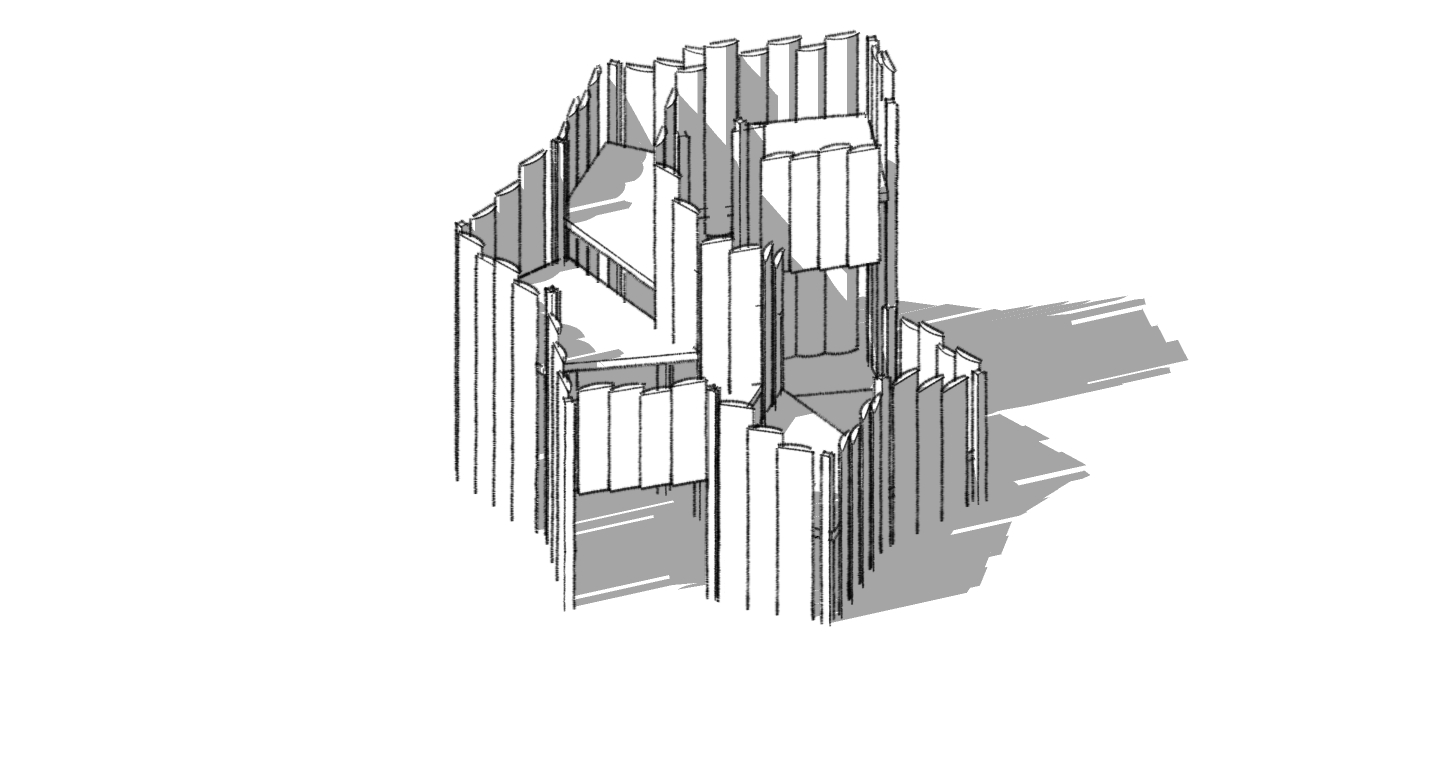

The latest computer model

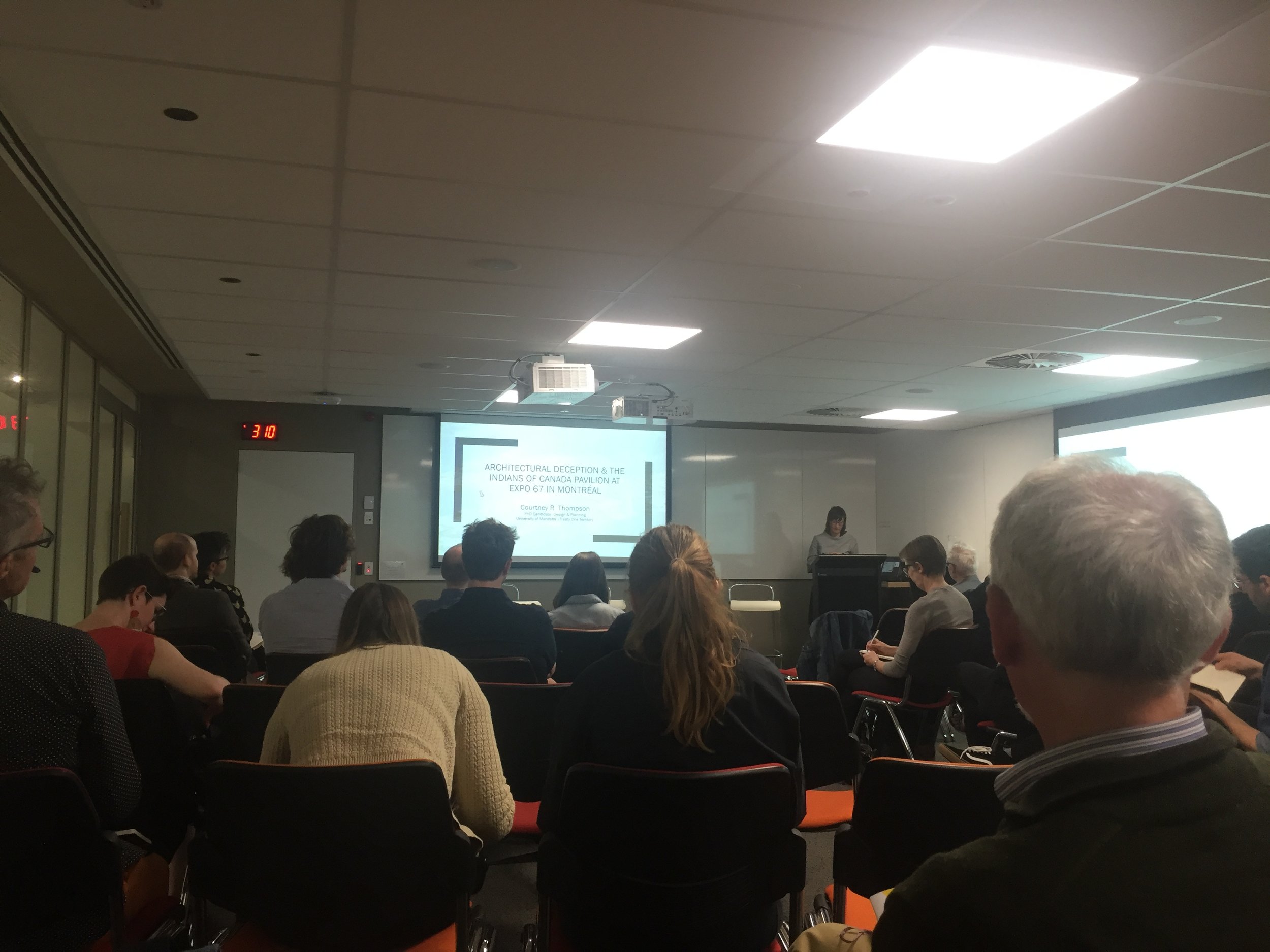

Courtney R. Thompson presents her paper on the Indians of Canada Pavilion.

The Values of Architecture

On Thursday & Friday last week I was invited to attend a conference organised by the School of Architecture at UQ. Speakers included Daniel Abramson from Boston University and Naomi Stead from Monash University.

https://www.architecture.uq.edu.au/filething/get/12573/Values%20Conference_%20Poster%20Schedule.pdf

Of particular interest was Courtney R. Thompson’s paper entitled ‘Architectural Deception and the Indians of Canada Pavilion at Expo ‘67 in Montreal’ - a critical review of the process by which this curious piece of architecture came into being as part of Canada’s centennial celebrations. The parallels are striking between the Canadian and Australian approaches indigenous cultural heritage and its place in the context a contemporary settler society.

Musing on the sound of hostile architecture - hard landscaping.

Radio reversal

I managed to squeeze in a conversation last Tuesday with Anna Carlson, an activist, artist, community organiser and political science researcher at UQ - also an old friend.

We spoke about the politics of sound in urban space - an unlikely marriage of my parallel lives as a musician, occasional acoustician, and would-be architecture researcher. The conversation was recorded for 4ZZZ radio, Brisbane’s longstanding community station:

http://www.4zzzfm.org.au/program/radio-reversal (about half way through @ -45:00)

I haven’t listened to it yet, but I suspect it’s long and rambling. The episode is available to listen for the next while. I’ll update the link above with a recording file when it expires.

Civic engagement

I met this morning with Pia Robinson, a visual artist, and Urban Designer with Brisbane City Council’s Public Art division. The discussion roamed far and wide: the challenges of promoting engagement around and through visual arts; equality of access to arts and culture and what that really means; the limitations of planning-led approaches to culture and the exciting possibilities of culture-led approaches to planning.

I talked through some of my ideas around the “infrastructures of ritual”, using the visual aid of drawings and images generated during the Pilot Study. The idea seems to offer fertile grounds for productive discussion. Pia gave me an overview of the various Council programmes she is involved with - the Outdoor Galleries, the Indigenous Art Programme, City of Lights, the River Art Framework, Curio-City, Botanica - and also explained the interface between the Public Art team and the Creative Communities team.

The Outdoor Galleries and associated laneway activations have been a particular focus over the past two years. We took a quick walk around some of the key locations: Burnett Lane, the King George Square carpark, Edward Street. Activations at each location are facilitated by an ‘infrastructural’ addition - light box galleries, glass vitrines, or street lighting for example - however, Pia made the point that the infrastructure alone was not enough to stimulate engagement on the part of the public or the average passer-by. She noted that the most engagement typically happens whenever there is some direct human contact or interaction as part of an artwork or activation - artist talks and public forums, walking tours, involvement in fabrication and making - in other words, shared participation.

Pia also noted the significance of access in determining the degree to which particular publics can engage with these kinds of activities - communities that are disadvantaged in terms of education, health, or financial security may not be able to readily access the city centre or the inner suburbs, where much of Council’s cultural activity is focused. Hence the dual importance of Council programmes aimed at outlying or marginalised suburbs, alongside improved and more affordable public transport options for those suburbs - a policy framework and an infrastructure to enable it.

It remains to be seen exactly what kind of engagement I will have with Council through the fieldwork - whether observation or participation. However, there is certainly some more fruitful discussion to come.

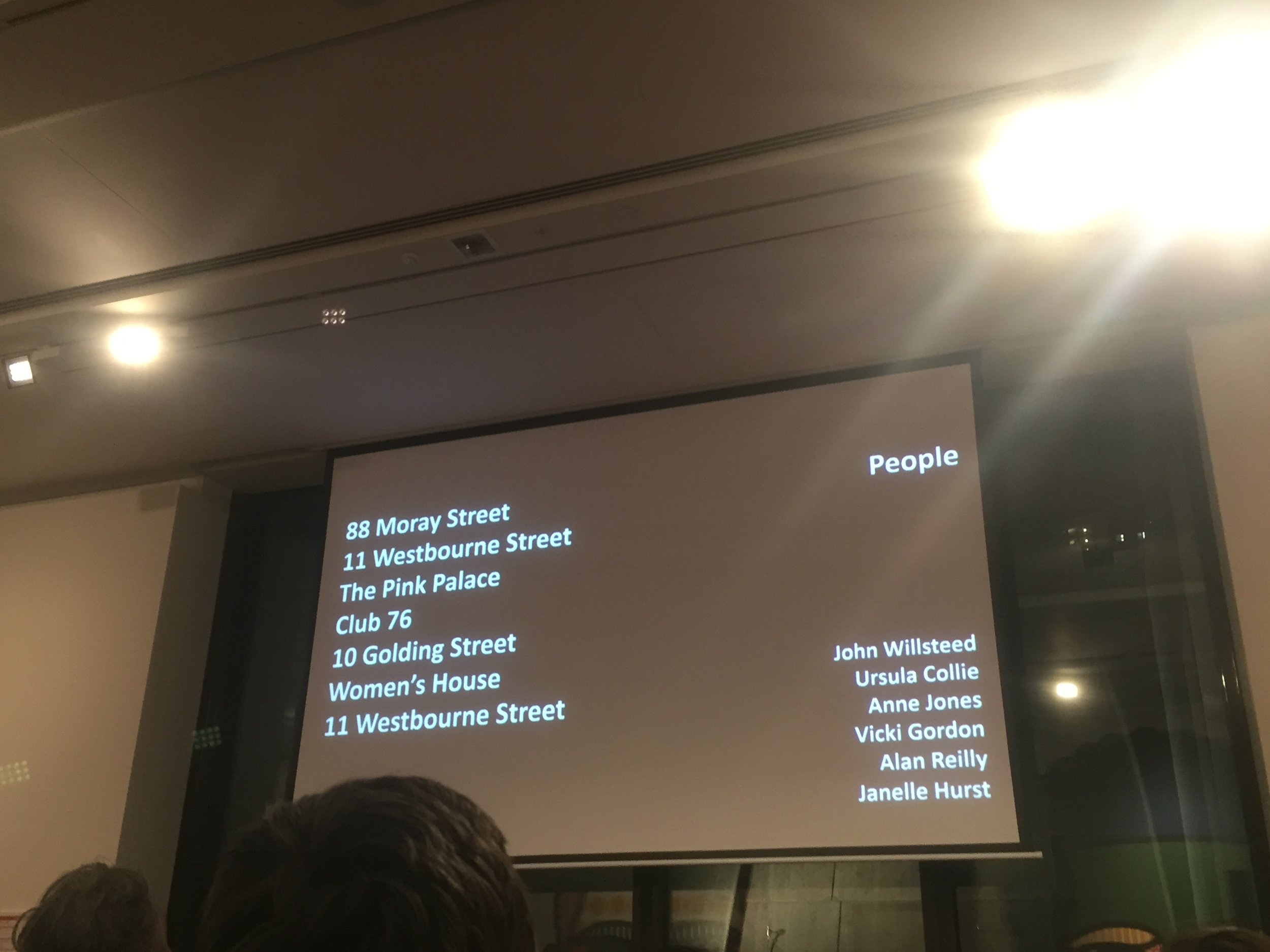

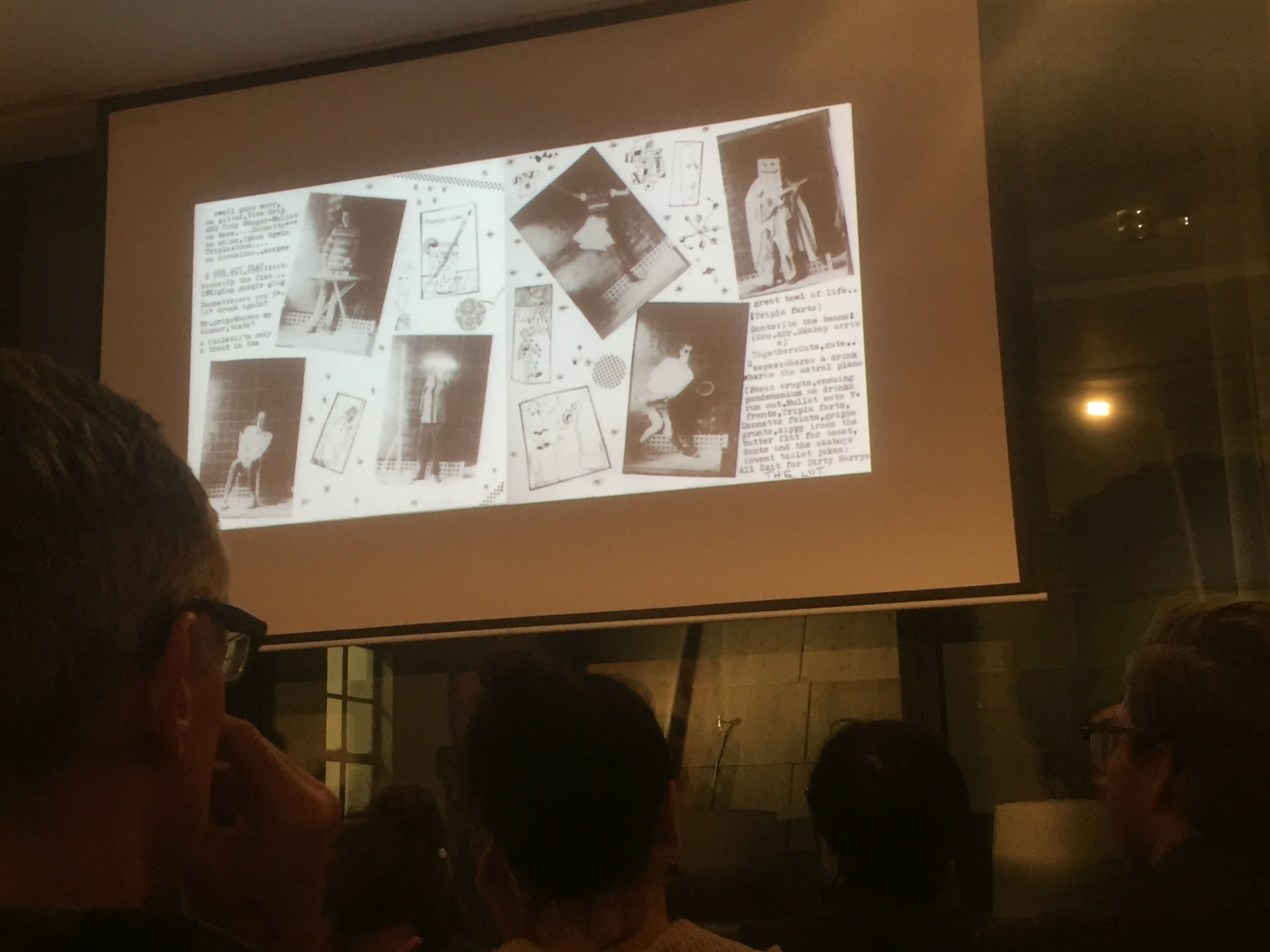

A slide from the Radical Houses reel showing a slogan typical of the period.

Brisbane’s Radical Houses

Last night I attended a forum at the Museum of Brisbane entitled Radical Houses: identity and public life in the Queensland House 1975-1989.

https://www.museumofbrisbane.com.au/whats-on/radical-houses/

Part of the inaugural Architecture and Art Week, the forum presented new research on a period of particular cultural vibrancy in Brisbane’s recent history and invited discussion of the Queenslander house as a site of public action and the making of political identity in the city.

The 1970s and 80s in Queensland are considered by many on the liberal left to have been a low point in the State’s history, often characterised as a period of quasi-fascist governance. Under conservative Premier Joh Bielke-Peterson, the state underwent a process of aggressive neo-liberalisation, similar to that of Thatcher’s UK and Reagan’s USA during the same period. In Queensland, this was accompanied by a famously oppressive regime of police harassment and brutality, underpinned by systemic corruption.

http://www.ccc.qld.gov.au/research-and-publications/publications/police/the-fitzgerald-inquiry-report-1987201389.pdf

Much of the evening was spent reminiscing about the good times. John Willsteed of celebrated Brisbane punk band the Go-Betweens offered a song.

The evening included presentations, performances, and panel discussions from several artists and musicians who were directly involved in radical activities at the time. The overarching narrative of oppression under ‘Joh and the Boys’ was apparent throughout the discussions. Several of the speakers described the political climate of the times as a “siege”. The artistic response to this was one of negation and self-destruction, or simply survival. The scrappy music and grotesque visual art they produced very closely resemble the familiar aesthetic of Punk. The DIY media publications (zines, mail art, etc) and theatre productions are steeped in anti-authoritarian satire - described simply as a political strategy of “taking the piss”.

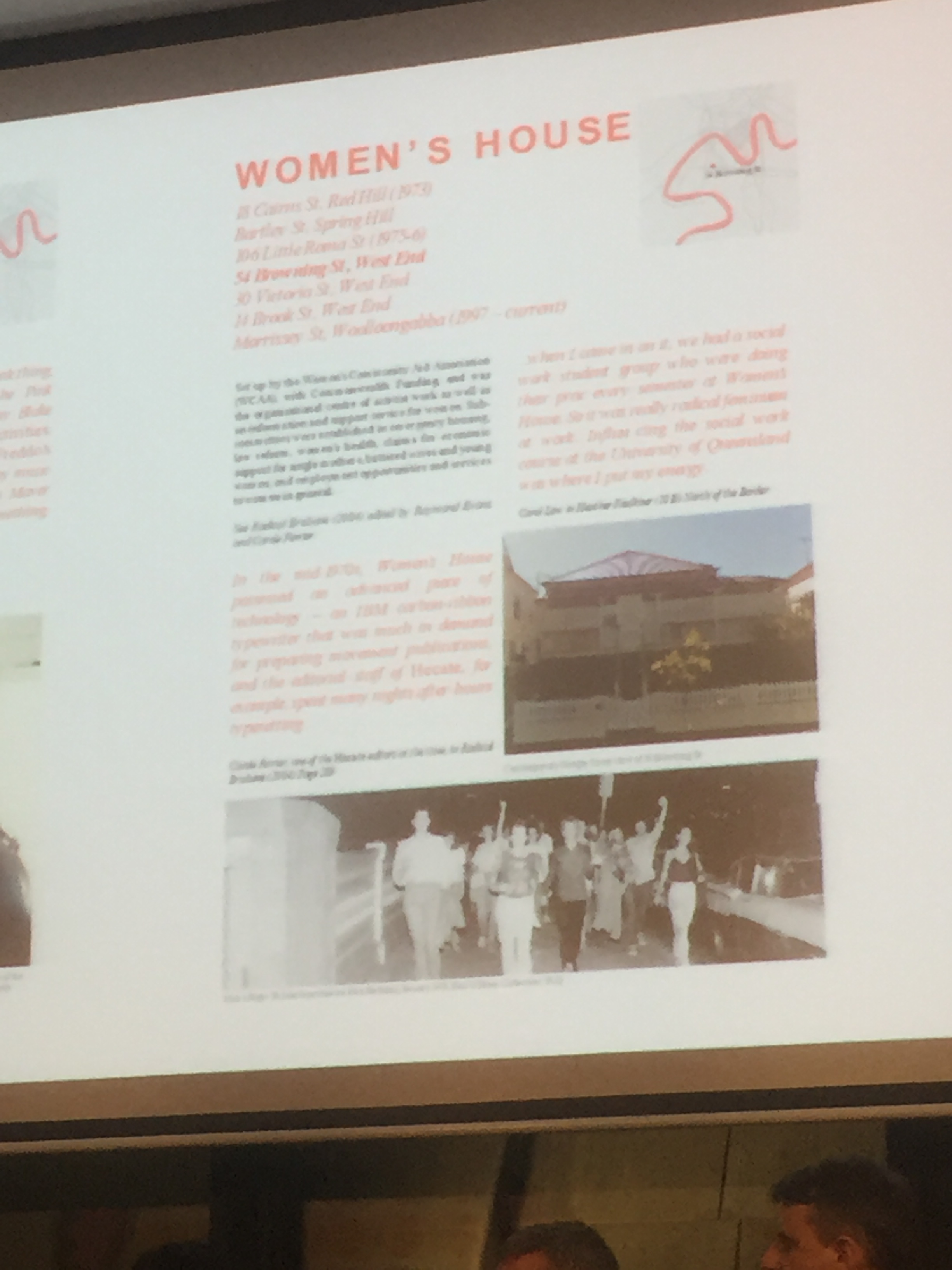

The Queenslander house was invoked as a facilitator of all this activity - cheap, inner-city, and spacious, the house became a test site for new ways of living and community-building, alongside artistic production, exhibition and performance. Against the backdrop of a suffocated civic realm, share-houses were a place to make new publics in the relative safety of the domestic realm.

Many of the panellists made this connection between the political environment and their lived artistic responses, positing that having something to fight against galvanised young people into action. However, only a few attempts were made at connecting this artistic activity back to specific political demands or progressive agendas. For many of those involved, the scope of ‘radical’ politics was simply the freedom simply to be oneself and to express one’s creative impulses. Similarly, no connection was made between the radical activity of the 1970s and 80s and the equivalent activity today. These pioneers of Brisbane’s radical housing culture laid the groundwork for a thriving underground from which important progressive art and politics continue to emerge, and yet they appear to be unaware of this legacy. By the same token, few of Brisbane’s artist-activists today make reference to their cultural inheritance or engage in direct dialogue with these radical predecessors.

The implication that young people had something to fight for ‘back then’ is that they don’t have something to fight for now. And yet, contemporary radical political and artistic movements continue to emerge from the underbellies of rented inner-city Queenslanders. People open their homes for gigs and exhibitions, everyone pitches in to build a veggie garden or cook a meal, people come and go by the open back door, the art and the music are scrappy and unfinished, the politics are personal. The parallels with the stories of the Radical Houses forum are uncanny, and yet there is an apparent failure to connect the past with the present (a recurring theme in Australian urbanism).

This disconnect raises an interesting prospect: If these ‘radical’ scenes have both effectively emerged in isolation, temporally separated but spatially overlaid, then perhaps the artistic response has less to do with the specific political context of the time and more to do with the particular qualities of the socio-spatial environment. Perhaps it is simply a case of young, well-educated people - many of whom have acquired musical or artistic training as part of their middle-class upbringing - taking advantage of the particularities of Brisbane’s built fabric and favourable property economics to do what young people do everywhere - rebel through revelry, and revel in rebellion.

Arguably the most telling moment of the evening was one response to a question regarding the relationship between the period of extraordinary cultural production described and the subsequent gentrification of the neighbourhoods in which this was taking place. Before I could finish asking what advice they might offer to younger artists and activists seeking to avoid this paradox, I was interrupted by one panellist with the words “suck it up”. She went on to describe how she and her fellow activists had intrinsically understood the value of Brisbane’s traditional built fabric, especially the Queenslander house, and thus had ultimately fought for its preservation by purchasing the homes they had once rented - an option beyond the realms of possibility even for relatively high earners of a younger generation.

This strikingly defensive response denotes a sense of entitlement that does not necessarily gel with the radical credentials put forth throughout the evening. It is an uncomfortable tension for many artist-activists that the cultural capital they generate in highlighting injustice are so often instrumentalised by injustice. However, it is much more uncomfortable to witness them disengage from the conversation altogether and resort to self-congratulatory nostalgia. People in Brisbane today do not have to contend with institutions as overtly corrupt and systematically violent as those of the past, and for that they should thank their radical predecessors. However, they still have plenty to contend with, much of it arguably more insidious - institutions that have taken on board and perfected the language of personal freedom espoused by the radicals of yesteryear, using it to sell a new image of the city to an aspirational elite of ‘global citizens’: emerging from the cultural cringe of its violent, parochial past, the new Brisbane is a veritable playground of individual consumption, a wonderland of the “creative industries” built upon deeply unsustainable forms of urban redevelopment that continue to dispossess, displace, and disintegrate marginal urban communities.

Temple Project - Workshop #1

This weekend I helped to kick start the Temple, a large-scale effigy built by BURN Arts Inc as part of Modifyre, an annual arts festival held in Inglewood, Qld - three and a half hours west of Brisbane. https://www.modifyre.org/

FRIDAY evening we had a get together for the volunteer build team and key representatives from other event teams including the Power Rangers (onsite power & lighting), FLAME (fire safety), DIC (Dept of Infrastructure and Construction), MAD (Modifyre Art Department), and RAD (Rapid Art Deployment), each of whom has input to various aspects of the final design.

SATURDAY was spent de-nailing, preparing and sorting salvaged timber - mostly from pallets and roadside scavenging - and evaluating what could be used for which parts of the structure. It was decided that considerably more material with a known structural performance would be required, and that the overall design had to be simplified to allow for easier assembly offsite - otherwise, virtually all the structural materials would be sourced from the hardwood mill in Inglewood, necessitating the crew travelling to site much earlier.

SUNDAY there was more material prep while we re-worked the concept model into something more achievable in the timeframe / budget.

Deliberating over the design of the Temple

Taking its initial cue from the work of David Best (first at the Burning Man festival in Nevada and subsequently around the world - https://davidbesttemples.org/), the Modifyre Temple is built each year by a team of volunteers over the course of just one month leading up to the event.

The Temple is a kind of monument to transience. It goes from conception to construction to conflagration in less than six months. During the week of the event (3-9 July), it serves as a repository for mementos and memorials to lost loved ones - a kind of vessel for personal and collective grief. At the event’s closing, the piece is then ceremonially burned as a symbolic gesture of release and catharsis. Often the fire is lit by participants who have lost friends or family in the last twelve months.

The first piece of this year’s Temple is assembled at HSBNE: a template for the six floor cassettes that will form a series of ascending viewing platforms.

Since March I have been mentoring the project lead Leonor (pictured above) in the delivery of the Temple, primarily via Skype and email. Leo is a graduate architect, but has never been to Modifyre nor led a team on a project of this scale. As such, I was asked to advise her on the design of the structure such that it is:

a) easy and quick to build, but still engaging for a team with widely varying levels of experience - from the carpenter with 30+ years experience to the first-time wood-worker;

b) feasible with primarily found / salvaged / recycled materials - and conceptually flexible enough to allow for the eventuality that some materials won’t be forthcoming;

c) cheap - BURN Arts runs its events on a shoe string - the overall project budget for materials & transport is just $1000; and

d) transportable in components using only pickup trucks and a 10’x6’ trailer.

In helping Leo to navigate these considerable design constraints, I have sought to connect her with the people and resources in Brisbane and Inglewood that she needs to realise the project - in particular:

Carpentry & general construction expertise

Structural engineering & timber design - for fire & live loads / climbability

Material suppliers - demolition yards, recycling yards, timber mills

Transport suppliers - folks in the community who might have utes, trailers or trucks available

Collaborators for illumination, sound, etc

The result has been a rapid design development process involving many different perspectives and culminating in a schematic design that appears to meet all requirements. Although the real test is when we actually try to build it..!

I am treating the process of collaborating on this project as a 1:1 design test within the framework of my own research. By documenting in detail the collective, often improvised, and intuitive process by which this project is designed and delivered by a community of volunteers, I aim to describe one version of this “infrastructure” by which we manifest ritual through architectural means.

The next workshops are this coming weekend. Ahead of that we’ll be drawing up the current schematic in greater detail in order to get specific quantities of fixings, put out feelers for specific material donations, confirm our onsite tooling requirements, and lock in logistics and transport.

I scream

On Friday I swung by West End to check the progress of West Village - a major masterplan development that was the subject of considerable controversy around its DA approval and subsequent call-in.

West Village was subject of my first case study, examining the aspirational ‘world-class city’ aesthetic and its influence on local planning procedures. After chatting with Dr. Kelly Greenop at the UQ School of Architecture this morning, it seems it continues to be a source of inspiration for theorists and commentators here - her second year architecture students are looking at “The Common” - West Village’s centrepiece - as an interesting example of privately curated open space in the city.

Phase two of West Village well underway. View from Mollison Street.

The unequivocally aspirational construction site hoarding.

Evidence of the popular Boundary Street Markets that occupied the Absoe site prior to redevelopment

The future of east brisbane

Yesterday was a busy re-introduction to all that’s happening in Brisbane.

First up, I attended a community meeting, “The Future of East Brisbane” in which Councillor Jonathan Sri addressed a group of local residents, outlining his vision for the area. The key issues raised for discussion were:

Disconnection - there is a perceived lack of a strong geographic community in the area. This was linked to housing stability (see below), but also to the deleterious effect of several major multi-lane roads cutting through the area, creating isolated pockets of suburbia with no associated public spaces / amenities accessible by foot.

Access / public transport - a map showing high-frequency transport (primarily bus) networks in the inner city made it clear that East Brisbane is something of a black hole as far as access goes. This means residents are entirely reliant on cars, despite living within 1km of the city centre.

Safety - both in terms of traffic and crime. High traffic volumes, both from local residents getting around the suburb and commuters coming through on one of the major arterial roads, make many local streets unsafe for kids to play or older folks to walk, meaning people tend to retreat from the street. The result is less passive surveillance and higher rates of petty crime, such as theft and vandalism.

Housing stability - 60% of East Brisbane (and the Gabba Ward as a whole) residents are renters, with an average tenure of 18months, so transience and precarious living situations are the norm. It was pointed out that this affects the entire community, as both settled and transient residents are unable to develop strong ties with their neighbours. Meanwhile, 1/8 houses in the area lies empty.

Sustainability and the localised effects of climate change - water restrictions (Queensland is often in drought), flooding (like other delta cities, Brisbane is braced for increasingly frequent and damaging floods due to rising seas), food security (over-reliance on trucked produce from dought-prone agricultural areas to the west), and increasing average summertime temperatures (Brisbane already regularly experiences regular 40 degree + days each year), were all raised as talking points.

Sri introduced some basic planning ideas aimed at “reimagining” the streets as pedestrian-friendly, localised and informal community spaces. These included narrowing streets to vehicles and introducing community planting / food growing initiatives in the (consequently wider) grass verges, reintroducing local businesses like corner shops by tinkering with commercial / residential zoning restrictions, and making existing public spaces such as parks more useable / less “anti-social” by introducing basic facilities such as barbecues, shade structures, and toilets.

Attendees at the meeting raised additional concerns around:

Loss of heritage buildings - particular more recent (1960s, 70s) buildings

Reinstating local business - how to encourage this?

Over-development - with reference to the proliferation of tower blocks currently under construction, and the associated increases in traffic volumes, etc.

Decision-making / input to the local neighbourhood plan.

Overall it was a very positive discussion, with lots of good ideas thrown around. It was interesting to note the extent to which the views and concerns of these mostly older, by standard measures “conservative”, residents actually align very closely with the proposals of a supposedly radical politician. In fact, in his calls to 'decentralise and localise’ both the economy and democracy, Sri is arguably calling for a return to a more traditional model of living - one that places decision-making in the hands of those whom it most directly affects.

ELEVATED pitch

Concept proposal for East Brisbane Bowls Club from my Pilot Study

Next I headed over to East Brisbane Bowls Club (EBBC) - home of Backbone Inc, a youth arts organisation working with emerging theatre makers and musicians (and the site for my Pilot Project concept proposal). I met with Backbone CEO and Artistic Director Kath Quigley and her colleague Stephen Quinn, the venue manager, to catch up on the latest goings on around the venue and the local area.

We discussed some of the current issues facing Backbone & the venue itself. Funding is an ever-present challenge, though the organisation remains inspirationally active and engaged with its target communities. However, the widening of Lytton Road continues to make much of this activity invisible to the local neighbourhood, particularly as much of it occurs in the evening - the venue simply looks like it is part of a construction site, completely cut off from both the street and Mowbray Park behind.

EBBC is not the only space suffering the consequences of the road widening though - the anchor café tenancy directly across the road has been vacant for 9 months, and local grocers, post office, and other small businesses (including an award-winning fish and chip shop!) facing the road have closed.

Using some of the sketches and images from my Pilot Project, I briefly introduced some of my thinking around how these issues might be highlighted through some kind of temporary intervention - perhaps a theatre set stretching between the river and the road (see above). We also discussed how such a project might fit in with their programme for the coming months. Two events in particular stood out as possible collaborations / case studies / design tests - Open Homes (Oct) and Backbone Festival (Nov).

~

Open Homes is a theatre project specifically prompted by the compulsory purchase and demolition of several nearby homes due to the road widening. It aims to open up local residents’ homes as a stage from which they can tell their own stories of place to a public audience. Each event is to be produced as a collaboration between Backbone theatre-makers and the residents themselves. Interesting opportunities for an intersecting documentation of both local lore and architecture.

Backbone Festival is the company’s big annual event, taking place over three weekends in November. It is a platform for young and emerging artists in Brisbane to develop new work. This might be a good opportunity to put some of the ideas of the Pilot Project into practice with Unqualified Design Studio, alumni of Backbone’s Open Source + Go programme.

RADICAL READING

BFU “term card” for 2019. Artwork by Mama See.

Finally, I rounded the evening off with some chewy discussion over a cup of tea and homemade cookies. The topic was police surveillance - something I haven’t considered much, but one which definitely presents some very interesting angles on the rhetoric of a New World City. Questions arose about the slavery / prison complex and its relationship to the settler-colonial nation-state: Is prison labour simply the 21st equivalent of slavery? Is this indentured labour more or less essential to the machinations of capitalism? What does it mean to “reform” an institution like the police? How can we ask these questions in the context of a society built on convict labour..?

Day one

Day one in Brisbane. Awoke to subtropical foliage outside the window.

The mid-winter here is the same as the Cambridge summer - 20 degrees and clear skies - just with days half the length.

Schedule for the day:

9:30am - Community forum “the Future of East Brisbane” organised by a local Neighbourhood Watch Group

4pm - meeting with Kath Quigley, CEO and Artistic Director of Backbone, a youth arts organisation, to discuss concept design proposals for East Brisbane Bowls Club

6pm - drop in to BURN Arts, Inc management committee meeting

6:30pm - Brisbane Free University Radical Reading Group.

Jet lag en route.

A patch of rainforest out the back of our temporary accommodation on Highgate Hill.